19.07.2017

Community-based sentences

7.5 All states and territories have sentencing regimes which enable some offenders to serve their sentence in the community.[2] Community-based sentences are generally categorised into ‘custodial’ (such as suspended sentences, home detention and intensive correction orders) and ‘non-custodial’ sentencing options.[3]

7.6 A suspended sentence, for example, is considered a custodial community-based sentence. This is because a sentence of imprisonment has been imposed, and then the execution of the sentence has been suspended.[4] The offender enters a good behaviour bond, which may include a requirement to participate in an intervention program.[5] Where the court revokes a good behaviour bond due to breach, the order suspending the execution of the sentence ceases to have effect.[6] The offender is then to serve the sentence in prison or the court can impose another form of custodial sentence (such as home detention).

7.7 Every state and territory has options for non-custodial community-based sentences.[7] For example, New South Wales (NSW) currently has Community Service Orders (CSOs) as one non-custodial sentencing option.[8] CSOs are not confined to cases that would otherwise result in a sentence of imprisonment, although it can only be imposed for offences that are punishable by imprisonment.[9] CSOs may require the offender to participate in personal development, education or other programs, and also may include such things as the removal of graffiti and the restoration of buildings.[10] There are mandatory conditions, including the requirement to report to corrective services; to be free of drugs or alcohol when reporting; and to follow directions.[11]

7.8 In NSW, an application to revoke a CSO may be made to the court by NSW Corrective Services on the grounds that the offender has failed—without reasonable excuse—to comply with their obligations under the CSO.[12] When an application is made, the court has a discretion to re-sentence the offender, taking into account that community service is no longer available. Although there is no presumption of imprisonment following a breach, breaches are taken seriously by the court, and may result in the offender being re-sentenced to a term of imprisonment.[13]

Justice procedure offences

7.9 JPOs refer to the breaching of custodial or non-custodial orders (and other offences against justice). JPOs are defined by the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification to include:[14]

breach of custodial order offences: including escape custody; breach of home detention or suspended sentence (by act or omission);

breach of community-based orders: including breaches of community service orders; breaches of community-based orders; and breaches of bail, parole or bonds;

breach of violence and non-violence orders (protection orders): including breaches of Apprehended Violence Orders, Domestic Violence Orders, and restraining orders;

offences against government operations: including resist or hinder government officials; bribery of government officials; immigration offences; failure to lodge census, tax form, vote; hoax calls; and postal offences; and

security and justice procedures other than justice orders: including subvert the course of justice; resist or hinder police; prison regulation offences; failure to appear in court.

7.10 Due to the impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, this chapter focuses on breaches of community-based sentences.

Impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

7.11 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are imprisoned for JPOs in greater proportions that non-Indigenous offenders:

In 2016, 13% (957) of all sentenced Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders prisoners were imprisoned for JPOs (as the most serious offence charged). This makes JPOs the third highest offence type for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders nationally, following acts intended to cause injury, and unlawful break and enter.[15]

In 2016, 9% (1,807) of the non-Indigenous prisoner population were imprisoned for JPOs—the sixth most common serious offence charged.[16]

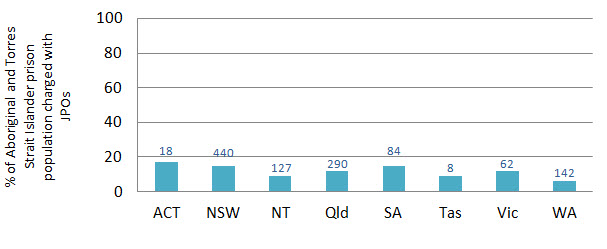

7.12 Imprisonment for JPOs is more prevalent in some states and territories. The percentage of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prison population imprisoned for JPOs and the number per state and territory is shown below.

Chart 1: Of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners, the percentage and number imprisoned for a Justice Procedure Offence (December 2016)[17]

Table 1: Of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners, the percentage and number imprisoned for a Justice Procedure Offence (December 2016)

| ACT | NSW | NT | QLD | SA | Tas | Vic | WA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number | 18 | 440 | 127 | 290 | 84 | 8 | 62 | 142 | 1171 |

Percent | 17% | 15% | 9% | 12% | 15% | 9% | 12% | 6% | 11% |

7.13 NSW has the largest number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people imprisoned for JPOs. Between 2001 and 2015, imprisonment for JPOs in NSW increased more than any other offence category during that time—more than doubling from 2001.[18] Most of the growth in prison numbers for JPOs by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people came from breach of community-based orders and breach of protection orders.[19]

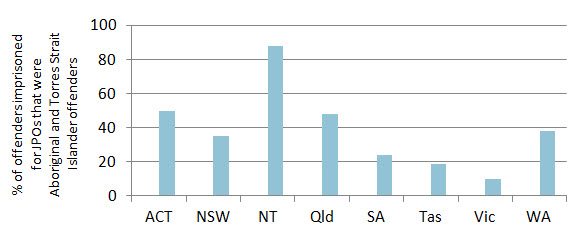

7.14 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were also disproportionately represented among prisoners charged with JPOs. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners represented 50% of all people imprisoned for JPOs in the ACT; 35% of all people imprisoned for JPOs in NSW; and 48% in Queensland. In all jurisdictions, the percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people imprisoned for JPOs was higher than the percentage of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoner population in that state or territory.

7.15 The proportion of JPO offenders in prison that were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people per state and territory is presented below.

Chart 2: The percentage of people imprisoned for JPOs that are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (December 2016)[20]

Table 2: The percentage of people imprisoned for JPOs that are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (December 2016)

| ACT | NSW | NT | Qld | SA | Tas | Vic | WA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Percent | 50% | 35% | 88% | 48% | 24% | 19% | 10% | 38% |

Circumstances related to breach of community-based sentences

7.16 In preliminary consultations, stakeholders in this Inquiry drew attention to the high imprisonment rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for non-compliance with conditions of community-based sentences. Stakeholders pointed to the possibility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders being subject to inappropriate conditions and programs while under sentence, combined with a lack of support, as a likely cause.

7.17 The circumstances outlined in the Western Australian Court of Criminal Appeal judgment in AH v Western Australia [2014] WASCA 228[21] provides such an example. In this case, a young illiterate and innumerate adult Aboriginal woman with complex needs, that included cognitive impairment and serious mental health issues, was sentenced to a community-based order following a short history of stealing cars. Under the order, the woman (AH) was to receive support from services and undergo treatment. AH had been suffering physical and mental abuse, had never been employed, was itinerant—living between two regional towns—and was unable to name all the months in a year, tell the time, and could not name the seasons. Services were not provided by corrective services as directed by the court under the order. She was, however, subjected to requirements to report at particular times. She did not comply, and subsequently stole another car. AH was sentenced to a further community-based order, under which services were again not provided, and AH again reoffended.

7.18 On the third occasion AH breached the community-based order, AH was sentenced to two years in prison. While in prison AH suffered a mental breakdown and an appeal was subsequently lodged. At the time of the appeal, AH was being held involuntarily in a mental health institution.

7.19 Information provided to the Court of Appeal showed that AH had initially reported to corrective services three days after her first appearance in court. At this meeting, she was told to come back one month later. AH failed to report and a warning letter was issued—the Court of Appeal decision noted that ‘sending a warning letter to an illiterate itinerant young Aboriginal woman with intellectual disability was an exercise in the utmost futility’.[22] AH was eventually found and directed to report on a date, which she missed and appeared the day after, she then failed to report on the next allocated date and made no further contact. During the appointments that AH attended, no assessment was made to determine her suitability for any programs nor was ‘any beneficial intervention proffered’.[23] This included any supervision or assistance with accommodation or any community support systems. The State neglected to put in place a guardian for AH. This inaction led the Court of Appeal to observe that ‘there was no shortage of reports, assessments and recommendations. What was missing was any action or oversight to implement those recommendations’.[24]

7.20 A similar turn of events followed the second community-based order. The Court of Appeal found that AH’s non-reporting was entirely predictable, and necessitated corrective services to organise some other way of making contact.[25]

7.21 The circumstances of AH’s case highlight some of the factors that may be causative of non-compliance by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with conditions of community-based sentences. Causative factors may include:

corrective services or other decision makers not setting relevant conditions and reporting requirements that are underpinned by the provision of services;

the lack of a coordinated service response in regional areas, and a lack of available services, particularly culturally appropriate services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women;

the impact of offenders’ mental health or cognitive impairment in understanding reporting requirements and other conditions; and

cultural and intergenerational factors that may result in transience and homelessness.

-

[2]

Crimes (Sentencing) Act 2005 (ACT) ch 5 pt 5.4, ch 6; Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) pt 2 div 3, pt 7; Sentencing Act (NT) divs 4, 4a; Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld) pt 5 div 2; Criminal Law (Sentencing) Act 1988 (SA) pt 6; Sentencing Act 1997 (Tas) pt 4; Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic) pt 3a; Sentencing Act 1995 (WA) pt 9.

-

[3]

The availability of community-based sentences to the court is discussed further in ch 4.

-

[4]

Judicial Commission of New South Wales, NSW Sentencing Bench Book [5-700]; R v Zamagias [2002] NSWCCA 17 [25].

-

[5]

See, eg, Criminal (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) pt 8.

-

[6]

See, eg, Judicial Commission of New South Wales, above n 4, [5-790].

-

[7]

With the exception of the Victorian sentencing regime, under which Community Correction Orders do not distinguish between custodial or non-custodial community-based sentences.

-

[8]

Criminal (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) pt 7. A new statutory sentencing regime for community-based sentences which aligns with Community Correction Orders in Victoria has been announced but not yet introduced by the NSW Government.

-

[9]

Judicial Commission of New South Wales, above n 4, [4-400]. With the exception of offensive language Summary Offences Act 1988 (NSW) s 4A and Fines Act 1996 (NSW) s 58(1).

-

[10]

See definition in Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999 (NSW) s 3; for a maximum of 500 hours: Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) s 8(2).

-

[11]

Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999 (NSW) s 108(a); Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2014 (NSW) cl 201.

-

[12]

Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999 (NSW)s 115(2)(a).

-

[13]

Judicial Commission of New South Wales, above n 4, [4-440].

-

[14]

Used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

-

[15]

Australian Bureau of Statistics, above n 1, table 10. Acts intended to cause injury, the highest at 33%, unlawful entry at 15% and offences against justice 13%.

-

[16]

Ibid. Of all sentenced and non-sentenced prisoners, 11% (1,167) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were imprisoned for JPO, compared to 8% (2,279) of non-Indigenous prisoners: table 8. It is noted that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners are less represented in drug and sexual offending offences.

-

[17]

Data source: Ibid table 15.

-

[18]

Don Weatherburn and Stephanie Ramsay, ‘What’s Causing the Growth in Indigenous Imprisonment in NSW?’ (Bureau Brief Issue Paper No 118, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, 2016) 6.

-

[19]

Ibid 3.

-

[20]

Data source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, above n 1, table 15.

-

[21]

AH v Western Australia [2014] WASCA 228 (10 December 2014).

-

[22]

Ibid [37].

-

[23]

Ibid [39].

-

[24]

Ibid [88].

-

[25]

Ibid [39], [122].