The Australian Law Reform Commission Final Report, Confronting Complexity: Reforming Corporations and Financial Services Legislation (Report 141, 2023), was tabled in Parliament today by the Attorney-General, the Hon Mark Dreyfus KC MP.

The report found that the legislation governing Australia’s financial services industry is a tangled mess — difficult to navigate, costly to comply with, and unnecessarily difficult to enforce.

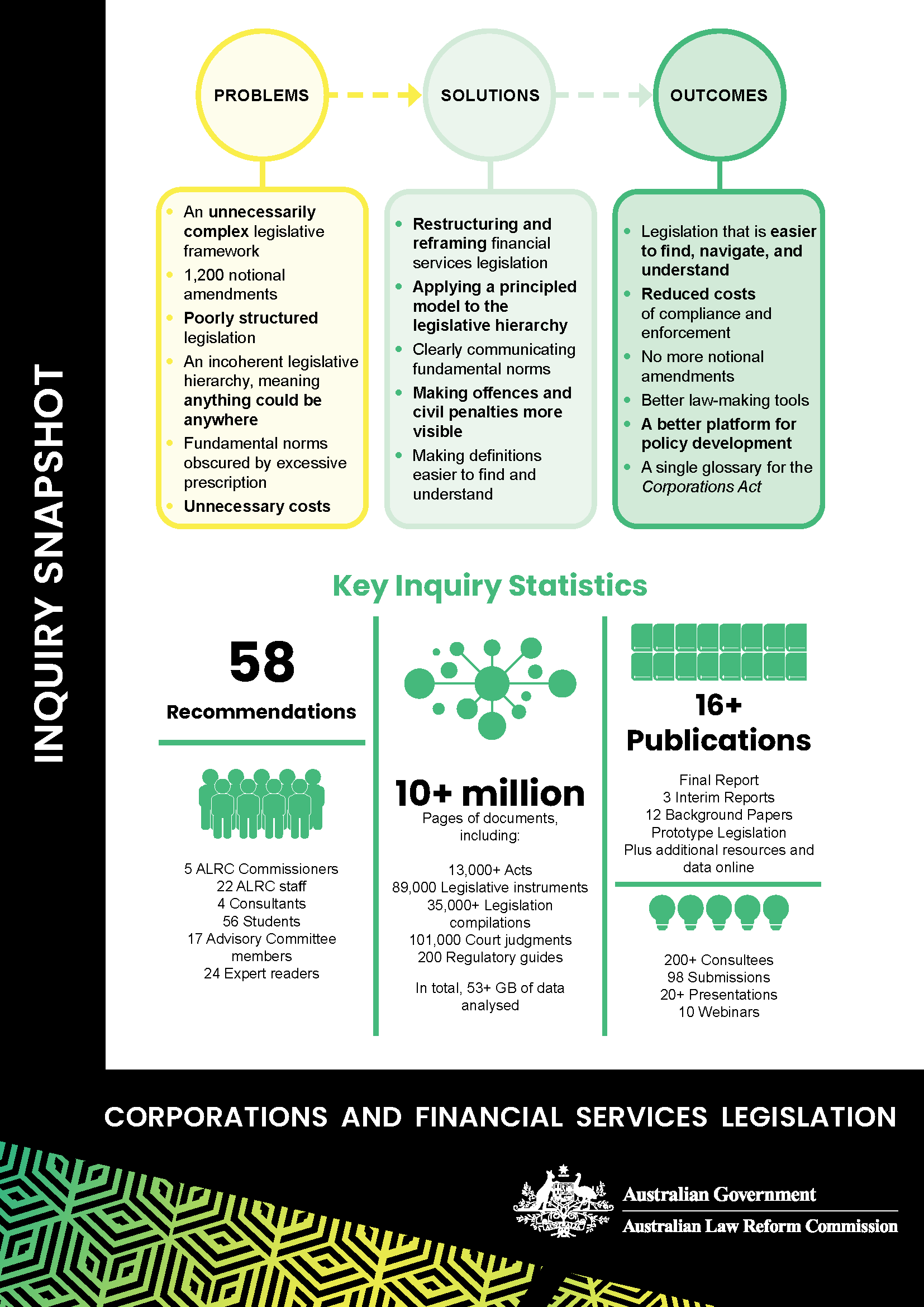

Judges have described the current laws as being like ‘porridge’, ‘tortuous’, ‘treacherous’, and ‘labyrinthine’. Others have described the legislation as ‘broken’. Complexity in the existing legislation is not an isolated problem — it costs businesses, consumers, investors, and the economy at large. The ALRC has made 58 recommendations to simplify the law, including a revamped legislative framework for the financial services sector. These reforms aim to reduce costs for service providers and consumers, improve productivity by reducing complexity, and provide clarity around compliance requirements and enforcement. Thirteen recommendations made during the Inquiry have already been implemented, in full or in part, by legislation passed during 2023.

Recommendations in the Final Report include:

- Redesigning financial services legislation to give it a clear home and identity as the ‘Financial Services Law,’ making it easier and less costly to find, navigate, and understand.

- Ending the use of almost invisible notional amendments that make the law deeply inaccessible, and instead using thematic, consolidated rulebooks to provide flexibility for regulating particular products, persons, services, or circumstances.

- Making it easier to tell when something is a ‘financial product’ or ‘financial service’ by introducing a single, simplified definition of both terms.

- Making offence and penalty provisions less complex and more obvious by consolidating them into a smaller number of provisions that cover the same conduct, making them easier to identify, and making the consequences of breach clear on the face of the law.

The report follows on from the findings of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation, and Financial Services Industry in 2019 that exposed the deficiencies of the current legal infrastructure.

Complexity costs consumers not only in the expenses that are passed on by financial services providers, but by failing to protect them from misconduct. The Royal Commission clearly demonstrated the economic and human costs of non-compliance with the law. The ALRC’s reforms would strengthen consumer protection substantially and reduce costs for business by making the law simpler to comply with and easier to enforce.

QUOTES — Justice Mordy Bromberg, President of the ALRC

‘Australia’s laws governing financial services are a confusing maze and need to be overhauled. The reforms outlined in this report will make these laws easier to understand and navigate, drive down the costs associated with complying with the law, and make it easier for consumers to understand and enforce their rights.’

‘These laws provide the legal and economic infrastructure of the financial services industry. The reforms we’re proposing are broadly supported by stakeholders and if implemented will see substantial improvements for both consumers and business.’

ENDS

Download the Final Report

Download the Summary Report

About the Australian Law Reform Commission

The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) is an independent Australian Government agency that provides recommendations for law reform to Government on issues referred to it by the Attorney-General of Australia.

|

Media contact: |

Francis Leach, Media and Communications Director comms@alrc.gov.au, 0409 947 180 |

Author: Dr Vannessa Ho

As the ALRC’s Financial Services Legislation Inquiry reaches its conclusion, it pays to look to the future. In an ever-evolving technological landscape, what will be the next challenge for financial services law? This article explores some recent innovations and the regulatory challenges they (and similar future developments) pose in the context of financial services law.

Continually evolving technologies

Technological advancements can lead to new or more efficient business practices in the financial services industry. However, the law can struggle to keep up with the fast pace of technological progress. This challenge is not new, and technology will continue to evolve in unanticipated ways. The question then becomes, how can financial services legislation be reformed to best accommodate continually evolving technologies?

The Australian Government has recognised the need to modernise financial services regulation. The ALRC’s forthcoming Final Report for the Financial Services Legislation Inquiry (‘Final Report’) seeks to outline reform that would produce a more adaptive legislative framework. Adaptivity in the face of technological development can help to support innovation and protect consumers from harm, thereby helping to ensure that markets for financial services operate efficiently and productively.

The regulatory challenges of evolving technologies

While financial services legislation should be technology neutral, challenges when regulating evolving technology persist. This is partly because it is difficult to determine how, and whether, legislation should regulate new technologies. There are also competing interests which may need to be considered before extending existing legislation to uses of new technology. For example, the law aims to protect consumers without imposing burdensome regulation that has the effect of stifling innovation. Three examples highlight the regulatory challenges of new technology: automated financial advice (commonly known as ‘robo-advice’); buy now pay later (‘BNPL’); and crypto assets.

Robo-advice

The term ‘robo-advice’ is used to encompass a wide range of technological capabilities. ASIC defines the term expansively to include ‘the provision of automated financial product advice using algorithms and technology without direct involvement of a human adviser’. Robo-advice can be used to provide financial advice on superannuation, other investments, mortgages, insurance, and credit products (see Ringe and Ruof’s article for further discussion on the current capabilities of robo-advice).

Robo-advice has the potential to benefit consumers as it could make financial product advice more affordable and convenient. This, in turn, could encourage more consumers to seek out financial advice before making important financial decisions. Further, with continual advancements in artificial intelligence, robo-advice seems likely to become more sophisticated, which may reduce the amount of human intervention needed when providing automated advice.

The existing legislative framework for financial services in Australia applies to robo-advice in the same way that it applies to human advice. This means that any weaknesses in the existing legislative framework would also affect robo-advice. Throughout the Financial Services Legislation Inquiry, the ALRC has highlighted how financial services legislation is unnecessarily complex. The legislative framework contains excessive prescriptive detail, is difficult to navigate, and costly to comply with. This complexity is likely to be a deterrent for firms that have the technological capability to enter the robo-advice sector.

There are many ways the existing legislative framework could be reformed to accommodate robo-advice. This article discusses the regulatory challenges associated with two options.

The first option would be to create bespoke legislation for robo-advice. The main challenge with this approach, however, is that robo-advice is still an emerging technology. The risks of a bespoke legislative framework for any emerging technology include:

- ensuring legislation is drafted to be sufficiently technology neutral, so that it does not become redundant as the technology evolves;

- if the legislative framework is restrictive or produces uncertainty, it may disincentivise firms looking to invest in research and development of the technology; and

- if legislation is too prescriptive, it is likely to require tailoring, exemptions, and carve-outs as the technology evolves.

The ALRC’s Inquiry has shown how excessive prescription and incoherent use of the legislative hierarchy to tailor regulatory regimes is a significant source of complexity. A more coherent approach to using the legislative hierarchy, such as that discussed in Interim Report B, would help to minimise this complexity.

The second option would be to maintain the current approach and continue to treat robo-advice in the same way as human financial advice. Under this option, reform could be made to the existing financial product advice regime. For example, the Quality of Advice Review discussed ‘digital advice’, which includes (and is sometimes used synonymously with) robo-advice. The Quality of Advice Review concluded that its recommendations would help facilitate digital advice. The Australian Government is now consulting further on the recommendations made by the Quality of Advice Review and potential changes to financial advice provisions in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act’).

Changes to financial advice provisions may be further supported by the ALRC’s reforms which aim to improve navigability and increase the adaptivity of the financial services legislative framework. A more navigable and adaptive legislative framework would facilitate the advancement of robo-advice technologies, and similar innovations, by making the legislation less costly to comply with.

Buy now pay later

ASIC describes BNPL as an arrangement that ‘allow consumers to buy and receive goods and services immediately from a merchant, and repay a [BNPL] provider over time’. Specific BNPL arrangements may vary depending upon what features the provider offers. However, consumers may seek to use BNPL because:

- it enables them to delay payment but obtain goods and services immediately;

- interest is generally not charged; and

- it can be easier to set up than a credit card or personal loan.

Many BNPL arrangements can fall outside the existing regulatory framework for financial services and credit. As a result, there are increasing concerns that BNPL may cause consumer harms, such as financial stress, hardship, and excessive fees. In response to these concerns and due to the similarity of BNPL with traditional credit facilities, the Australian Government has committed to extending the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (‘NCCP Act’) so that it captures BNPL arrangements. However, due to the variety of BNPL arrangements, there may be challenges when extending the existing credit regime. These challenges are likely to include:

- defining the concept of BNPL to ensure it encompasses a sufficiently broad range of business models;

- tailoring the responsible lending requirements of the NCCP Act to protect consumers without stifling innovation; and

- preventing unnecessary legislative complexity from creeping further into the credit regime, with the aim of avoiding the level of complexity that has developed within the Corporations Act.

Crypto assets

As highlighted in the ALRC’s Background Paper ‘New Business Models, Technologies, and Practices’, crypto assets can be defined in different ways and for different purposes. Crypto assets have also been variously referred to as digital assets, virtual assets, tokens, or coins. One description of crypto assets, advanced by Treasury, is that it

is a digital representation of value that can be transferred, stored, or traded electronically. Crypto assets use cryptography and distributed ledger technology.

Treasury has more recently undertaken a token mapping exercise to examine the crypto ecosystem within Australia and its intersection with existing financial services legislation. The token mapping exercise developed an understanding of the key concepts of crypto assets and related terms like crypto networks, tokens, and token systems. This exercise is a step towards policy development for the regulation of crypto assets within Australia.

The existing definitions of ‘financial product’ in Australian legislation are framed in technology neutral terms. This means that crypto assets are capable of meeting these definitions and falling within the existing regulatory regime. Regulatory challenges largely stem from the wide variety of crypto assets and the subsequent difficulty in reaching a settled definition. The obstacles caused by developing a coherent definition of crypto assets may be somewhat resolved by Treasury’s token mapping exercise. However, Treasury has noted that some types of token systems may not fit within the existing framework.

Following the token mapping exercise, Treasury released a consultation paper on a proposal which seeks to ‘introduce a regulatory framework to address consumer harms in the crypto ecosystem while supporting innovation’. Rather than regulate crypto assets directly, Treasury proposes to regulate crypto exchanges via the Australian Financial Services licensing regime, thereby requiring crypto exchanges to meet a licensee’s obligations and requirements within the Corporations Act. Regardless of the form this proposal takes, it is still important that the legislative framework be adaptive to support innovation of the crypto economy.

What could be done?

The regulatory challenges of evolving technologies highlight the importance of an adaptive, efficient, and navigable legislative framework. This is the case for technologies that fall within the existing legislative framework (such as robo-advice) and technologies for which policy is being developed (such as BNPL and crypto assets). The findings of the ALRC’s Inquiry demonstrate that the existing legislative framework for financial services is unnecessarily complex — it is difficult to navigate, hard to understand, and key principles are often buried in prescriptive detail. Adaptation in the existing legislative framework often takes the form of complex notional amendments and conditional exemptions, spread incoherently across the legislative hierarchy. This increases the costs of compliance and creates barriers to innovation.

The ALRC’s Final Report will contain recommendations aimed at reforming the existing legislative framework so that it is more adaptive, efficient, and navigable. The ALRC’s recommendations will focus on:

- restructuring and reframing financial services legislation to better communicate its core requirements and emphasise fundamental norms of behaviour;

- creating more coherent and principled use of the legislative hierarchy, making the legislative framework easier to navigate and more adaptive (without generating unnecessary complexity); and

- ensuring definitions are easier to find and understand.

Conclusion

The are many benefits of using evolving technology to innovate and enhance productivity. Tempered against these benefits, however, is a need for sufficient consumer protection where there is risk of significant harm. The ALRC’s forthcoming Final Report will discuss how the existing legislative framework for financial services legislation is unnecessarily complex. In the context of evolving technology, this complexity can stifle innovation and productivity, and undermine consumer protection. Complexity in the existing legislative framework also makes it harder to implement policy initiatives aimed at regulating emerging technologies. The reforms recommended by the ALRC in the Final Report aim to produce an adaptive legislative framework for financial services that can support innovation, policy development, and consumer protection more effectively than at present.

Author: Jane Hall

Emojis are ubiquitous in modern communication. In 2021, Unicode reported that 92% of the world’s online population use emojis. Emojipedia estimates that over 900 million emojis are sent each day without text on Facebook Messenger, and that by mid-2015, half of all comments on Instagram included an emoji.

Given how frequently we use emojis, it should come as no surprise that emojis are making their way into the law (a recent episode of the Law Report on Radio National explored this development). A recent decision of the King’s Bench for Saskatchewan made headlines when the court determined that the 👍 emoji could be a legally binding indication of agreement to a contract (see South West Terminal Ltd v Achter Land & Cattle Ltd [2023] SKKB 116). This decision was one in a growing line of cases where courts have been asked to interpret the meaning and legal effect of different emojis (see Eric Goldman, ‘Emojis and the Law’).

This article explores another potential use for emojis: legislative drafting. The ALRC is currently preparing its Final Report in the Financial Services Legislation Inquiry. Throughout the Inquiry, the ALRC has explored ways to improve the navigability and comprehensibility of legislation. If emojis are already cemented in our daily lives, could they also help make legislation easier to navigate and understand?

After examining how the law has started to use emojis and other images, this article considers:

- 🥸 the characteristics of good legislation and the goals of legislative design;

- 🎨 how emojis could be used in legislation; and

- 🏆 whether emojis could help achieve the goals of good legislative design.

While emojis may improve the navigability and comprehensibility of legislation, these benefits are (for the foreseeable future at least) likely to be outweighed by the additional uncertainty 🫤 and ambiguity 🙃 emojis introduce.

🤔 Why consider using emojis in legislation?

Emojis are not just playful devices to express our sense of humour, or to send subliminal messages. They can have serious legal consequences.

For example, in In re Bed Bath & Beyond Corp. Securities Litigation, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 129613 (D.D.C. July 27, 2023), the US District Court found that the use of the ‘full moon face’ emoji (🌝), in a Tweet by the respondent, Cohen, about shares in a particular company could be understood by shareholders as an indication that the stock would increase in value and that shareholders should therefore buy or hold stocks. The Court stated:

In the meme stock “subculture,” moon emojis are associated with the phrase “to the moon,” which investors use to indicate “that a stock will rise.” So meme stock investors conceivably understood Cohen’s tweet to mean that Cohen was confident in Bed Bath and that he was encouraging them to act.

In South West Terminal, the Court determined that the 👍 emoji could act as a signature on a contract for the delivery of flax. The court recognised that the use of the 👍 emoji was a ‘non-traditional’ means of signing a contract but that nonetheless, in circumstances where the parties had previously reached similar agreements via text message, it was a valid way to convey the purposes of a signature.

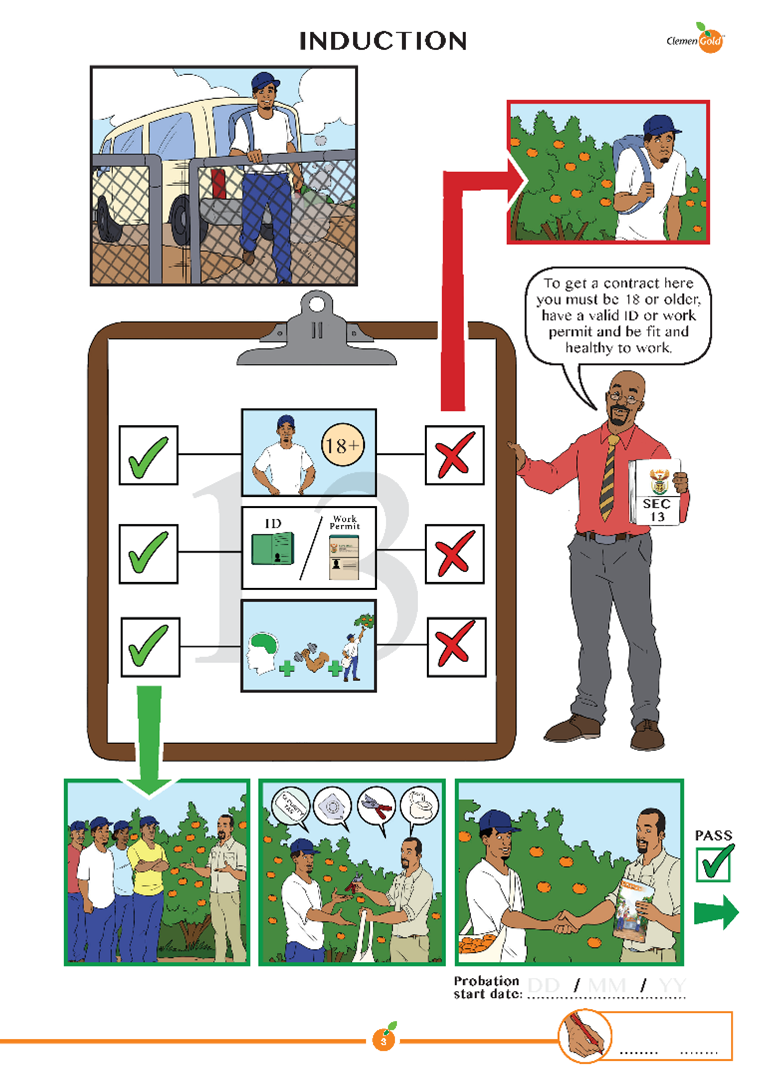

These cases can be seen as part of a broader trend of embracing images to affect legal interactions and to make the law more accessible. Initiatives such as Comic Book Contracts and Creative Contracts have been exploring the use of visual and cartoon-based contracts. Cartoon-based contracts use images to convey the key terms of the contract. Sometimes the images are accompanied by simplified text but other times the contract only contains images. These types of contracts have been particularly useful for linguistically diverse workplaces. For example, Creative Contracts developed an employment contract for a citrus farming business in South Africa, a country in which multiple languages are spoken. The cartoon-based contracts produced by Creative Contracts ‘reduced the induction time from four hours to 40 minutes’, reflecting the potential for images to effectively convey information.

Source: Creative Contracts (https://creative-contracts.com/clemengold/)

In 2018, Aurecon and the University of Western Australia co-designed the first employment contract for an Australian workplace that combined text and images to make concepts like probation and leave entitlements more easily comprehensible to a workforce that did not have legal training.

Legislative drafters too have been experimenting with different ways of presenting information to improve the ‘readability’ of legislation. For example, guidance from the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel emphasises the use of ‘readability aids’, which includes the use of visual aids such as flow-charts (see, eg, Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ch 3, which uses a flowchart to show how the Chapter applies to particular evidence).

If we are already using emojis in ways that affect legal relations and to develop contracts, and we’re already experimenting with different readability aids, it begs the question: is the next logical step to use emojis in legislation? Could emojis help to make legislation more accessible?

🥸 What does good legislation look like?

The question ‘what makes for good legislation’ will be answered differently depending on who you ask. In this article, I assess the quality of legislation by reference to how easy it is to access and use.

The ALRC has previously published on good legislative design and user-friendly legislation, and has proposed seven working principles for the structuring and framing of corporations and financial services legislation in Interim Report C. This article focuses on the concept of ‘mental models’ that enhance the navigability and comprehensibility of legislation. I consider that good mental models focus on the following:

- 👌 simplicity (improving the coherence and clarity of the legislation);

- 💡 comprehensibility (highlighting important matters that may not be immediately apparent); and

- 🧭 navigability (both within and between Acts).

These three elements will form the criteria for assessing the potential effectiveness of emojis in legislative design.

🎨 How could emojis be used in legislative drafting?

Using emojis in legislative drafting does not mean turning legislation into a visual cryptic crossword by replacing all references to ‘Australia’ with the 🦘 or 🐨 emoji, or substituting the 🧑⚖️ emoji for the word ‘court’. Rather, emojis could be used as visual aids, or signalling devices, to improve the navigability of legislation by:

- ❗ highlighting important matters, such as offence provisions;

- 🔎 identifying matters that may not be immediately apparent on the face of the provision, such as defined terms or notional amendments; and

- 👩🎨 improving the visual appeal of legislation.

🧪 Case study: section 791A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)

To illustrate what this could look like, I took a current provision from the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and inserted emoji ‘signals’. The provision is currently located in Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act, a chapter described as being like an old cupboard in need of a good spring clean 🧹.

The provision currently reads:

Emojis could be used as signalling devices to highlight the following:

|

Information |

Emoji |

|

Section 791A is a civil penalty provision |

🚫 |

|

Sub-section (1) contains an obligation |

⚠️ |

|

The provision contains terms that are defined in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) |

📖 |

|

The provision contains terms that are defined in other legislation |

📘 |

|

The provision was introduced after the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) was enacted and has been subsequently amended |

📝 |

The reframed provision could look like the following:

Does it work?

The reframed provision appears to partially satisfy the criteria for a good mental model:

|

|

Aim |

Achieved? |

|

|

Simplicity |

Coherence and clarity |

🤔 |

While the emojis are useful signalling devices, they remove some whitespace and may make the provision seem crowded. There is a risk of ‘information overload’. |

|

Comprehensibility |

Highlight important matters that may not be apparent on the face of the legislation |

✅ |

The emojis highlight that the provision contains obligations and offence provisions, and that it has been amended since its enactment. |

|

Navigability |

Improve navigability within the Act and with other Acts |

🤔 |

The emojis identify terms that are defined within this Act, and tell users that certain terms are defined in other Acts. But, the emojis are quite distracting, an issue the ALRC has previously noted when it comes to identifying defined terms. |

👎 The downsides

While there is certainly a case for using emojis to assist with the simplicity, comprehensibility, and navigability of legislation, embracing emojis in legislation comes with some potential downsides. Goldman identifies five key issues with the use of emojis in law more generally:

- 🕵️ visual decoding (emojis are relatively small in size and several emojis look quite similar, which can make it difficult to identify which emoji has been used);

- 👯♀️ multiple meanings (there is no definitive reference source catalogue for emojis and Unicode’s criteria for accepting new emojis suggests that it prefers emojis that have multiple potential uses);

- 😵💫 depiction diversity (emojis appear differently on different platforms, which can increase confusion as to their intended meaning);

- 💂♀️ culture-specific meanings, which inform metonyms (using emojis as a form of figurative language to replace words or expressions, such as using the 🤔 emoji instead of the phrase ‘hmm’ or ‘let me think’ – see Javier Morras and Antonio Barcelona, ‘Emojis: Metonymy in Meaning and Use’); and

- 🖊️ unsettled grammatical rules when using multiple emojis in a thread.

The first three of these issues are particularly relevant for emojis in legislation.

Visual decoding may undermine the potential for emojis to be useful signalling devices in legislation. If it is difficult to identify which emoji has been used, then readers will not benefit from the visual prompt.

For example, the 📝 emoji (which in the example above indicates that the provision has been amended since the statute’s enactment) could be confused with another writing-based emoji, such as: 📃📄📜🗒️. At best, this may result in users of legislation simply ignoring the emoji. At worst, it could result in confusion and uncertainty.

Multiple meanings could create ambiguity and uncertainty.

For example, while in South West Terminal the 👍emoji was interpreted as a signature on a contract, in Lightstone RE LLC v Zinntex LLC, 2022 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 5925 (N.Y. Supreme Ct. Aug. 25, 2022), the Supreme Court of New York considered that the same emoji did not constitute acceptance of a contract in circumstances where the surrounding text messages showed that the sender did not intend to be bound by the agreement. Even in South West Terminal there was argument about whether the 👍emoji should merely be interpreted as a confirmation of receipt of the text message.

Such ambiguity could be mitigated through an interpretive provision being inserted into the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) to explain what the emojis indicate. Such a provision could be along the lines of:

Use of emojis

If a provision of an Act includes an emoji, the following table provides the meaning of the emoji in the particular context.

|

References to Emojis in Acts |

|||

|

Item |

If the provision uses the following emoji |

in the following context |

then the emoji indicates … |

|

1 |

📝 |

in the margin next to a provision title |

that the provision has been amended since enactment |

|

2 |

📖 |

in the margin of a provision followed by certain terms |

that those terms are defined terms within the Act |

|

3 |

📘 |

in the margin of a provision followed by certain terms |

that those terms have a defined meaning in another Act, which applies to this Act |

|

4 |

⚠️ |

in the margin of a sub-provision |

that the sub-provision contains an obligation |

|

5 |

🚫 |

in the margin of a sub-provision |

that the sub-provision is an offence provision |

However, it may be unrealistic to expect that users of legislation would instinctively turn to the Acts Interpretation Act to resolve any confusion they have as to the meaning of an emoji that appears in an Act. It is more likely that users would rely on their own understanding of the emoji, which could differ significantly from another user’s understanding, or would run a search on the internet to learn the meaning. This would lead to further issues because legislation would be giving the emoji a new, context-specific meaning that may differ from what users would understand to be the ‘ordinary meaning’ of the emoji.

Another option would be to use ‘hover boxes’ to show the intended meaning of the emoji. However, this may be limited by the current capabilities of the Federal Register of Legislation.

Depiction diversity would likely cause issues because users of legislation may not recognise the emoji if its depiction in legislation differs from the way that the emoji appears on a user’s platform.

For example, the ‘full moon face’ emoji referred to in South West Terminal is depicted quite differently on various platforms:

|

Apple |

Microsoft |

|

Noto Emoji Font |

|

Twitter/X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

If we are going to use emojis in legislation, we may need to accept that the depiction that is chosen is likely to be recognisable to people familiar with that platform but may be unrecognisable or confusing for people familiar with a different platform, or who do not use emojis at all. The ability of users to recognise the emoji, and to understand its meaning, would therefore depend on (a) whether that person uses emojis at all, and (b) which platform the user is most familiar with. This would seem to undermine the purpose of using emojis: to increase the accessibility and navigability of legislation. It is also at odds with the principle that legislation should be generally accessible and comprehensible by all users.

The combined effect of these three issues is to produce a level of ambiguity and legal uncertainty that seems to outweigh the benefits emojis could bring to legislation.

💭 Conclusion

Parts of the Commonwealth statute book are in need of an upgrade and an update. The ALRC is currently reviewing financial services legislation in an attempt to make it easier to navigate and understand. The question is, could emojis help achieve those aims? 🤔

In the case of financial services legislation, any improvement to navigability and comprehensibility would seem to be outweighed by the increased ambiguity and uncertainty that emojis would introduce😞 .

While emojis may not be the solution for reforming financial services legislation, there could be a case for using emojis as legislative signalling devices to help bring legislation into the twenty-first century 🪄 . I commend anyone brave enough to attempt that feat 👏 .

Data collection and analysis have been crucial in the ALRC’s inquiry into the legislative framework for corporations and financial services regulation. During the Inquiry, the ALRC partnered with leading academics and consumer advocacy group CHOICE to commission survey research of consumer understandings and experiences with financial services and the legislative framework for their regulation.

The results of that survey are in, and they are analysed in detail in the submission of Associate Professor Andy Schmulow, Professor Therese Wilson, Nicola Howell, Professor Nina Reynolds, and Dr Paul Mazzola now available for download.

The survey and submission are particularly focused on fairness in the provision of financial services. Of note, the survey reveals that those who reported experiencing unfair treatment were also more likely to have lower expectations of how financial institutions should behave. In general, survey participants felt that the performance of financial service providers fell short of their expectations.

The ALRC extends its sincerest thanks to the submission’s authors for conducting the survey and analysing the results. The ALRC is also grateful to CHOICE and the more than 2,000 anonymous survey participants.

Both the ALRC and CHOICE contributed funding for the survey and assisted in formulating the questions asked of participants in the survey.

The submission will help to inform the ALRC’s Final Report for this Inquiry, which is due by 30 November 2023.

Human rights practitioners and policymakers have long considered how to ‘balance’ human rights when they intersect or overlap. But what if we have been using the wrong metaphor to guide this important work?

As part of the ALRC’s Inquiry into Religious Educational Institutions and Anti-Discrimination Laws, the ALRC and Wolters Kluwer hosted a webinar to hear from international human rights experts on how to best maximise the realisation of all rights in the context of religious educational institutions.

In launching this discussion, former UN Special Rapporteur of freedom of religion and belief, Professor Heiner Bielefeldt (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg), queried whether the ‘balancing’ metaphor presumes that human rights interact in a zero-sum manner in which one right must be compromised to allow for the other. If so, this act of balancing may detract from the aspiration that all humans enjoy all rights to the maximum extent possible.

Reframing the ‘balancing’ of rights as the ‘maximising’ of all rights, moderator Professor Carolyn Evans (Griffith University) led Professor Heiner Bielefeldt and Professor Lucy Vickers (Oxford Brookes University) through an exploration of international perspectives on how rights can be maximised in the provision of education and employment in religious educational institutions. This discussion responded to questions posed by webinar attendees such as:

- What happens when rights to non-discrimination and religious freedom interact? How are limitations on rights managed in the context of religious educational institutions?

- The child is a right holder as is the parent, how do these right interact?

- What is the role of the state as a guarantor of rights? How relevant is the child’s right to education?

- How does religious freedom permit religious educational institutions to cultivate a community of faith and when can religious freedom be limited

- If there is tension between rights to non-discrimination and religious freedom, should this be resolved by an individual leaving a religious educational institution? Does this protect all rights?

Like Australia, countries around the world have grappled with the question of how anti-discrimination laws should apply to religious educational institutions. This engages a range of overlapping rights including the right to freedom of religion or belief, right to non-discrimination, right to education, children’s rights, and right to privacy. Different jurisdictions have – informed by their own histories and institutional structures – approached this task in different ways, leading to a range of legal frameworks.

Join the ALRC, Wolters Kluwer, and leading international experts in the fields of human rights and equality law for a live webinar to discuss international perspectives on maximising the realisation of overlapping rights in religious educational institutions.

Critical issues we will also explore include:

- The interactions of institutional autonomy and individual religious freedom;

- Equality obligations in education;

- Respecting parents’ and childrens’ rights and;

- Preferencing staff to maintain a community of faith.

Speakers:

- Professor Lucy Vickers, Professor of Law, Oxford Brookes University, United Kingdom

- Professor Heiner Bielefeldt, Professor of Human Rights and Human Rights Policy, University of Erlangen, Germany. Former UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief.

Expert Moderator: Professor Carolyn Evans, Vice-Chancellor and President, Griffith University

Participants are invited to ask questions of speakers. Cannot attend the webinar? Register to receive the recording.

Restructuring and reframing the legislative framework for financial services

Why does the structure and framing of legislation matter?

What are the problems with the current structure of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act?

How can financial services legislation be made easier to navigate and understand?

On Monday 10 July 2023, the ALRC hosted a webinar to examine Interim Report C and what it means for you.

Watch the recording to hear about the ALRC’s proposals for restructuring Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act and creating a Financial Services Law, in pursuit of a more user-friendly legislative framework for financial services.

The live online audience was invited to ask questions of the ALRC panel.

Discover further detail about how the key reforms proposed by the ALRC — including the ALRC’s proposed legislative model discussed in Interim Report B — may be implemented.

Australian Public Law Blog Article by Sarah Fulton and Geneviève Murray

Judicial impartiality — and within that, an absence of bias — is at the heart of the Australian judicial system and central to how judges see themselves. But while serving and retired judges of the High Court have had a lot to say about when judicial bias arises, they have (with some notable exceptions, as noted in the ALRC Judicial Impartiality Report, p 234) said little publicly about how such matters should be raised with and considered by the courts. Until now.

In QYFM v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2023] HCA 15 (‘QYFM’), judges of the High Court not only clarified the law on apprehended bias as it applies to a judge who was previously involved in the prosecution of a party, but also took the opportunity to set out their views on the processes for determining issues of bias raised in multi-member courts (such as Courts of Appeal, Full Courts, or the High Court itself).

Restructuring and reframing the legislative framework for financial services

Monday 10 July 2023 at 1.00pm AEST

| Register now |

Everyday objects are easier to use if they are well designed. The same is true of the law.

Join the ALRC to examine Interim Report C and what it means for you. Hear about the ALRC’s proposals for restructuring Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act and creating a Financial Services Law, in pursuit of a more user-friendly legislative framework for financial services.

Ask questions, as the panel outlines further detail about how the key reforms proposed by the ALRC — including the ALRC’s proposed legislative model discussed in Interim Report B — may be implemented.

Topics of discussion include:

- Why does the structure and framing of legislation matter?

- What are the problems with the current structure of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act?

- How can financial services legislation be made easier to navigate and understand?

Chair:

- The Hon Justice Craig Colvin, Part-time Commissioner, Australian Law Reform Commission and Judge, Federal Court of Australia

Panel:

- Christopher Ash, Principal Legal Officer, ALRC

- Ellie Filkin, Legal Officer, ALRC

- Nicholas Simoes da Silva, Senior Legal Officer, ALRC

Submit your questions to the panel on registration or via financial.services@alrc.gov.au.

Ellie Filkin and Christopher Ash

Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) is like an old cupboard: it is crammed full and poorly organised, with insufficient time set aside for the occasional spring clean. While the first few boxes fit in this cupboard, over time the containers have become mislabeled and inconsistently sorted. More and more law has been packed into old suitcases, tattered boxes, and shabby bags. The cupboard contains more than it was ever designed to hold.

The sense of dread when opening a messy cupboard is the same feeling that confronts many users of Chapter 7. Interim Report C is, fundamentally, about how the cupboard that is Chapter 7 could be better organised so that users can find what they need without having to go through every box of old CDs and cassette tapes.

Today, the ALRC launches the third (and final) interim report as part of its Review of the Legislative Framework for Corporations and Financial Services Regulation. Like Interim Report B, a central theme of Interim Report C is finding the right ‘home’ for different parts of the law. Interim Report C focuses on Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act (concerning financial services regulation), but many of the law design principles examined by the Interim Report are relevant to legislation more generally. This article reflects on some of these principles, and other findings of the Interim Report.

Stakeholders are invited to make submissions on the proposals and question in Interim Report C by 26 July 2023.

|

Financial Services Legislation: Interim Report C (ALRC Report 140) Submissions open until 26 July 2023. |

Legislation should be as easy to navigate and understand as possible

There are practical and principled reasons for why legislation should be as easy to navigate and understand as possible. Legislation that takes longer to find and understand costs more to comply with. Laws that are hard to find, or once found can only be understood with difficulty, are unlikely to achieve their purpose. Legislation that is hard to find and understand also runs contrary to rule of law principles.

Even experts in financial services law have told the ALRC that they have difficulty navigating Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act. As the ALRC’s Inquiry has shown, users of Chapter 7 must sift through too much poorly organised prescriptive detail to find and understand their core rights and obligations.

Interim Report C applies some of the approaches from human-centred design — commonly used in non-legal fields —to show how financial services legislation could be made more user-friendly and, ultimately, more effective.

Unpacking financial services legislation

From the outside, Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act looks thematically consistent: it regulates financial products, financial services, and financial markets. However, thematic consistency at that high level is unhelpful, and has produced a chapter that — at 254,000 words — is longer than all but nine Commonwealth Acts. As the Chapter’s contents have expanded, more has simply been placed into existing boxes, particularly those relating to financial products and services. Compared with every other substantive chapter in the Corporations Act, Chapter 7 simply does too much.

Even where provisions within Chapter 7 are grouped together in a way that makes sense, core obligations are often obscured by administrative and procedural detail. Exceptions are sometimes placed prior to the rule, and specifics before more general (and fundamental) obligations. A reformed structure is needed to better organise existing provisions and accommodate future policy developments.

Financial services providers and consumers face the additional problem that Chapter 7 is not the only Act they must consult to find the relevant law. The ASIC Act — focused largely on establishing the financial services regulator — contains many of the most fundamental standards of commercial behaviour for financial services providers and many protections for consumers. The fact that several of these provisions overlap with provisions of Chapter 7 compounds the difficulty of understanding the law.

The current structure of financial services legislation means finding the relevant law takes longer than it should, and once found the law is still unnecessarily complex and difficult to interpret and understand. Law that is unnecessarily difficult to understand is less likely to be followed. Such non-compliance can result in policy failure and harmful consequences for consumers, businesses, and the effective functioning of markets. Increased resources associated with navigating, understanding, and applying unnecessarily complex legislation increases costs for financial services providers, which are in turn passed on to consumers.

Repacking financial services legislation

The ALRC suggests that financial services legislation should find a new home and legislative identity in a schedule to the Corporations Act — to be known as the Financial Services Law (Proposals C9 and C10). This new home would allow a reformed structure and framing to be implemented, less burdened by the drafting styles and ad hoc legislative design choices of the past. Moving can be a lot of work, and so the ALRC’s implementation roadmap shows how it could best be done.

Interim Report C identifies several areas of existing legislation that should be grouped together to make the legislation easier to navigate and understand. These topics should form separate chapters of the Financial Services Law, covering consumer protections, disclosure, financial advice, and general regulatory obligations. If the Financial Services Law were not adopted, this grouping could also be undertaken within the existing body of the Corporations Act (either as chapters or parts within a chapter), although such an approach is likely to be less effective.

Consumer protection

Consumer protections lie at the heart of financial services legislation, and the fundamental norms that they embody resonate throughout the legislative framework. Generally applicable consumer protection provisions have the broadest application, and typically provide a cause of action and remedy directly to consumers. Such protections should be intuitively grouped together and easy to locate, particularly given their relevance to consumers who may be unfamiliar with the legislation. Currently, however, these provisions are spread between various provisions of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act and Part 2 Div 2 of the ASIC Act.

The ALRC proposes consolidating Part 2 Div 2 of the ASIC Act with consumer protection provisions currently in Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act (Proposal C1). The ALRC also suggests that several consumer protections, such as the prohibitions on misleading or deceptive conduct (Proposal C2) and unconscionable conduct (Proposal C3), could be consolidated to express their normative significance more forcefully. These measures would help to improve the navigability and communicative power of consumer protection provisions.

Financial advice

The fact that Parliament has made a concerted effort to create a legal framework for financial advice is far from clear on the face of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act. The original Chapter 7 included almost no provisions specifically regulating financial advice, and as such it has never had a logical ‘home’ for these provisions. As the regulation of financial advice has developed, provisions have been slotted in among other topics, without any hints as to where financial advice provisions are located or how they fit together. The ALRC suggests that provisions relating solely to financial advice should be reframed and grouped into a financial advice chapter (Proposal C6).

Disclosure

The provisions relating to disclosure for financial products and services in Chapter 7 are some of the most unnecessarily complex and least coherent provisions of the Corporations Act. Their complexity makes it difficult and costly for regulated persons to navigate and understand disclosure obligations. Restructuring and reframing disclosure provisions into a single legislative chapter (Proposal C4) is an area where reform represents substantial ‘bang for your buck’.

The ALRC also suggests that the framing of disclosure provisions could be improved by making explicit what is currently implicit: namely, by making clear the outcome — consumer understanding — that disclosure documents are meant to produce (Proposal C5).

General regulatory obligations

General regulatory obligations underpin how financial services providers conduct their business. The ALRC proposes that the range of general regulatory obligations currently spread across financial services legislation should be more coherently organised into two legislative chapters (Proposals C7 and C8). Alongside the creation of a chapter focused on consumer protection (Proposal C1), this would be central to a more navigable and comprehensible legislative framework.

User-friendly design

Adopting the logic of human-centred design, each reformed chapter (or part) should be structured and framed with the needs of users in mind. The ALRC proposes several law design principles that would help achieve this (Proposal C14). For example, provisions should be ordered so as to prioritise core obligations and norms, with administrative and procedural matters given lesser prominence. Obligations should not just appear in ‘shopping lists’ — rather, their order should reflect their relative importance and scope of application. Prescriptive detail should be separated from core obligations, with legislative notes and other aids to interpretation used to signpost where further information is located.

Dedicated removalists

Anyone who has moved house would attest that the process is much easier when you have the right people to help. It is reassuring to know that your valuables are in safe hands and won’t get damaged or lost along the way. Restructuring and reframing financial services legislation should be treated with the same level of care.

The ALRC proposes that a dedicated taskforce (or taskforces) should be formed to oversee the staged reform of financial services legislation (Proposal C12). This would allow expertise and stakeholder involvement at each step of the process. Partnerships between the public sector, industry, and academic expertise would help to maintain momentum throughout the reform process.

Conclusion

In short, Interim Report C shows how unpacking and repacking financial services legislation could make it more user-friendly and a less daunting prospect for those who open its doors. If we leave the task any longer, the cupboard will only become even more crammed and jumbled.

To learn more, download the ALRC’s Interim Report C (in both summary and complete forms). The ALRC welcomes submissions in response by 26 July 2023.