10.10.2016

Introductory statement

The ALRC’s annual performance statement is prepared for paragraph 39(1)(a) of the PGPA Act for the 2015–16 financial year and accurately presents the ALRC’s performance in accordance with subsection 39(2) of the PGPA Act.

ALRC purpose

The ALRC purpose is to review Commonwealth laws as referred to it by the Attorney-General for the purpose of making recommendations about law reform that will contribute to a fair, equitable and accessible system of federal justice and a just and secure society.

The ALRC has one outcome:

Informed government decisions about the development, reform and harmonisation of Australian laws and related processes through research, analysis, reports and community consultation and education (Outcome 1).

In delivering this outcome, the ALRC provides evidence-based reports that outline recommendations for law reform to contribute to an equitable and accessible system of federal justice and the harmonisation of Australia’s laws and practices. In this way the ALRC contributes to the Attorney-General’s mission—achieving a just and secure society.

The ALRC has one program to achieve its outcome:

Conducting inquiries into aspects of Australian law and related processes for the purpose of law reform (Program 1).

It is through the inquiry process that the ALRC is able to undertake the research and analysis that underpins recommendations for law reform and provides the basis for informed government decisions.

Performance criteria

Implementation rates

The ALRC tracks the implementation of its recommendations over time. Implementation rates are an indicator of the effectiveness of the ALRC in achieving its objective as the rate of implementation provides evidence of the ALRC’s relative success in facilitating informed decision-making by Government that leads to development, reform and harmonisation of Australian laws and related processes.

Citations

The number of citations of ALRC reports provides an indication of the relevance of ALRC work to legal proceedings and judgements.

Submissions

The number of submissions received is one indicator of the breadth of the evidence base that underpins the ALRC’s recommendations and of community engagement with law reform.

Visitors to website

The number of visitors to the ALRC website is an indicator of the community’s engagement with the work (past and present) of the ALRC. This engagement underpins and gives confidence to informed government decision-making.

Presentations and speaking engagements

Presenting at public conferences, seminars and parliamentary inquiries ensures that the work of the ALRC is publicly debated and discussed.

Media mentions

The number of media mentions provides an indicator of community engagement in the ALRC’s work and contributes to the community’s knowledge about the Government’s law reform agenda.

Criterion source

The ALRC’s Performance Criteria are sourced from the ALRC’s Corporate Plan 2015–19 and Portfolio Budget Statements 2015–16 p 225.

Result against performance criteria

See Table 2, KPI performance 2015–16.

Table 2: KPI performance 2015–16

KPI measure | 2015–16 target | 2015–16 actual |

|---|---|---|

Implementation of reports | 85% | 86% |

Citations or references | 50 | 56 |

Submissions received | 150 | 75 |

Visitors to website | >250,000 | 1,143,519 |

Presentations and speaking engagements | 25 | 29 |

Media mentions | 250 | 243 |

Analysis of performance

The ALRC does not self-refer inquiries, and can only undertake inquiries that are referred to it by the Attorney-General. Therefore, the ALRC’s performance from year to year will be affected by the Government’s law reform agenda and the number of inquiries referred to the ALRC and the prescribed timeframe as indicated in the Terms of Reference.

It is usual for the ALRC to work on two inquiries at any one time, as indicated in our Corporate Plan and Portfolio Budget Statements. However, in some years, the Attorney-General may refer more than two inquiries to us, or less, and this will affect our performance against our targets.

The subject matter of an inquiry may also have an impact on our performance against our targets. Some inquiries concern issues of broad general interest in the community, or are highly contentious, or attract a specific industry’s focus and the community’s engagement with the inquiry is high. This may result in many submissions being received and more consultations being undertaken. Other inquiries attract a lesser community response, with fewer submissions received but are nonetheless still significant. Therefore, the ALRC’s performance will be affected from year to year by circumstances outside of its control.

2015–16 is one such year when for much of the year, the ALRC was only referred one inquiry by the Attorney-General—a Review of Commonwealth Laws for Consistency with Traditional Rights, Freedoms and Privileges (the Freedoms Inquiry). This was not forecast in our 2015–16 Corporate Plan and PBS and was the result of a one-off government efficiency measure that saw the ALRC’s budget reduced for the 2015–16 financial year. Consequently, some of our targeted performance criteria have been affected—particularly the number of submissions received. Receiving 50% of the target correlates directly, in this case, to only conducting one inquiry.

That the impact has not been as detrimental as it may have been is due to the energy, commitment and sheer hard work of the ALRC team and the engagement of our stakeholders in the Freedoms Inquiry and then in the early stages of the Elder Abuse Inquiry.

A report on the ALRC’s Freedoms Inquiry is at Appendix C.

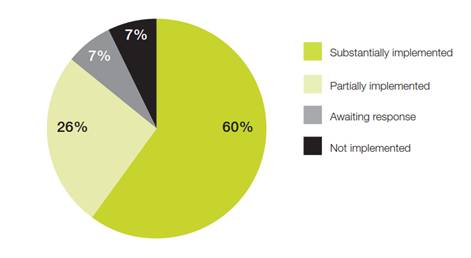

Implementation of reports

The ALRC has no direct role in implementing its recommendations. There is no statutory requirement for the Australian Government to respond formally to ALRC reports. However, the ALRC monitors major developments in relation to issues covered in its past reports, and assesses the level of implementation that those reports have achieved. It is not uncommon for implementation to occur some years after the completion of a report.

The ALRC considers that a report is substantially implemented when the majority of the report’s key recommendations have been implemented by those to whom the recommendations are directed. Partial implementation refers to implementation of at least some recommendations of an ALRC report. The term ‘awaiting response’ refers to reports that have been completed within the past ten years in relation to which the ALRC is yet to receive a formal response from the Government. The term ‘not implemented’ refers to reports that were completed over ten years ago and have not had a response from the Government.

The levels of implementation of all ALRC reports are as follows:

60% are substantially implemented;

26% are partially implemented;

7% are awaiting response; and

7% have not been implemented.

Chart 1: Implementation status of ALRC reports as at 30 June 2016

These figures represent an overall implementation rate for ALRC reports of 86%. The Government has yet to respond to a number of recently completed ALRC reports, including Making Inquiries: A New Statutory Framework (ALRC Report 111, 2010); Secrecy Laws and Open Government (ALRC Report 112, 2010); Copyright and the Digital Economy (ALRC Report 122, 2014); Serious Invasions of Privacy in the Digital Era (ALRC Report 123, 2014); Equality, Capacity and Disability in Commonwealth Laws (ALRC Report 124, 2014); Connection to Country: Review of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (ALRC Report 126, 2015); and Traditional Rights and Freedoms—Encroachments by Commonwealth Laws (ALRC 129, 2016).

Appendix D provides a detailed update on action in relation to ALRC reports during 2015–16.

A brief overview of the implementation status of all 87 inquiry-related ALRC reports can be found on the ALRC website at www.alrc.gov.au/implementation-final-reports.

Court citations

Past ALRC reports are cited by Australian courts and tribunals as well as in numerous academic articles and other publications.

During 2015–16, there were at least 56 mentions of ALRC reports in the judgments of major Australian courts and tribunals.

These included citation in five cases in the High Court of Australia, seven in the Federal Court of Australia or the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia, three in the Family Court of Australia and 28 in state and territory Supreme Courts or Courts of Appeal, as well as in the decisions of other major courts and tribunals, such as the NSW Industrial Court, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal of Australia and state civil and administrative tribunals.

The total number of citations in 2015–16 is lower than the number of judgments from Australian courts and tribunals referring to ALRC reports reported in 2014–15, when there were at least 77 mentions of ALRC reports in the judgments of federal, state and territory courts.

The ALRC report most often cited across the Australian courts, as in previous years, is Evidence (Interim) (ALRC Report 26, 1985) as it assists the judiciary by informing them of the background of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and state and territory uniform Evidence Acts. The ALRC’s later reports on evidence, Evidence (ALRC Report 38, 1987) and Uniform Evidence Law (ALRC Report 102, 2006) are also cited frequently. For example, in IMM v The Queen [2016] HCA 14, the High Court referred to ALRC Reports 26 and 38 when considering the definition of ‘probative value’ in the Evidence (National Uniform Legislation) Act (NT).

A number of the ALRC’s early reports continue to be cited by the courts, including ALRC Report 2, Criminal Investigation, cited by the High Court of Australia in North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Limited v Northern Territory [2015] HCA 41. More recent reports cited by the courts include Family Violence: A National Legal Response (ALRC Report 114, 2010), and Managing Discovery: Discovery of Documents in Federal Courts (ALRC Report 115, 2011).

A list of these court and tribunal citations can be found in Appendix E.

Mentions in Parliament

During 2015–16, ALRC reports and recommendations were referred to in the following Committee proceedings:

interim report of the Senate Standing Committees on Economics relating to the classification of computer games;

report of the Senate Standing Committees on Legal and Constitutional Affairs on a phenomenon colloquially referred to as ‘revenge porn’;

advisory report of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security on the Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment Bill (No. 1) 2015;

report of the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs on the child support program; and

report by the Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs on violence, abuse and neglect against people with a disability in institutional and residential settings.

Submissions

The number of submissions received by the ALRC is a measure of public engagement with its work and the extent to which the consultation papers have stimulated debate and discussion. However, the number of submissions received for any inquiry is also influenced by its subject matter—particular inquiries are likely to generate a greater, broader degree of public interest and participation than others.

Table 3: Submissions received 2015–16

Consultation paper | Submission closing date | Submissions received during reporting period |

|---|---|---|

Traditional Rights and Freedoms—Encroachments by Commonwealth Laws (ALRC Interim Report 127) | 3 August 2015 | 75 |

Total submissions received |

| 75 |

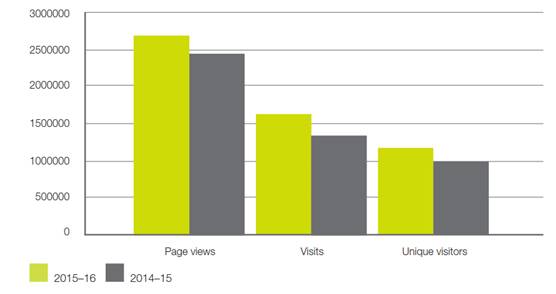

ALRC website

The ALRC website is a pivotal communication tool for the ALRC and a law reform resource for the wider public. The ALRC strives to continually build value into the website, both in terms of providing useful and accessible content relevant to stakeholders and researchers, and utilising its functionality as an online consultation tool.

Key website metrics for 2015–16:

visits = 1,598,726

page views = 2,670,750

unique visitors = 1,143,519

These metrics represent, compared to the 2014–15 reporting period:

22% increase in visits

10% increase in page views

20% increase in unique visitors

Chart 2: Comparison of website traffic: August–June in 2014–15 and 2015–16

ALRC website statistics provide evidence that it is not just in implementation that the ALRC makes a significant contribution to law and legal frameworks in Australia.

In 2015–16, the top five reports accessed by PDF downloads were:

1.Serious Invasions of Privacy in the Digital Era (ALRC Report 123)

2.Traditional Rights and Freedoms—Encroachments by Commonwealth Laws (ALRC Interim Report 127)

3.Uniform Evidence Law (ALRC Report 102)

4.Family Violence: A National Legal Response (ALRC Report 114)

5.Seen and Heard: Priority for Children in the Legal Process (ALRC Report 84)

The inclusion in this list of the Uniform Evidence Report from 2006 and the Seen and Heard Report from 1997 illustrates the enduring value of the ideas, discussion and research contained in these landmark reports.

Presentations and speaking engagements

Presenting at public conferences, seminars and parliamentary inquiries ensures that the work of the ALRC is publicly debated and discussed. During 2015–16, ALRC Commissioners and staff made 29 presentations at a range of events around the country. They also contributed 7 articles to a range of journals and publications. A full list of presentations and articles is at Appendix F.

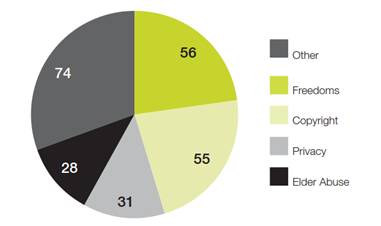

Media mentions

The ALRC actively promotes public debate on issues raised by its current and past inquiries, and on law reform generally.

During 2015–16, the ALRC identified 244 mentions of its work across a range of media. This represents a decrease of 15% from the previous reporting period. This decrease is best explained by the fact the ALRC has only worked on one inquiry at a time during this reporting period.

The Freedoms Inquiry attracted most media attention (30%), as both the Interim and Final Reports were released during the reporting period. The 2012 Copyright report attracted 22.5%, due to the release during this period of the Productivity Commission’s report which largely supported the ALRC’s key recommendations.

The Elder Abuse Inquiry attracted 11% of the media attention, however it is worth noting that this Inquiry commenced more than midway through the reporting period.

In 2015–16 privacy law reform continued to rate highly in the public interest, with the recent Inquiry into Serious Invasions of Privacy in the Digital Era and the ALRC’s 2008 Privacy Inquiry together garnering 13% of media attention.

The ALRC conducts its own media monitoring. An archive of 2015–16 online media mentions is available on the ALRC website.

Chart 3: Media mentions per inquiry 2015–16

Significant developments and challenges for 2016–17

During 2016–17, the ALRC will complete its Inquiry into Elder Abuse in May 2017 and will work on any further inquiry referred to it by the Commonwealth Attorney-General.The ALRC will also finalise a new Enterprise Agreement.

The challenge for the ALRC is that it does not set its own work program but is reliant on the Attorney-General’s referrals. Therefore it is the Government’s reform agenda and timelines which determine the number and scope of inquiries that are referred to the ALRC, and this affects the ALRC’s ability to meet its performance expectations. The ALRC would normally work on two inquiries concurrently, however as of June 2015, the ALRC has only had terms of reference for one inquiry at any one time. This has affected the number of submissions we have received which were half of what had been predicted.

The ALRC expects to be referred another inquiry in 2017 and a second inquiry once the Elder Abuse Inquiry is completed. In that event the ALRC will return to its usual mode of operations.

In addition, the Government’s own program and priorities determine both when and how it considers completed ALRC inquiries, and the schedule for any implementation. This means that the rate of implementation of ALRC reports is in the hands of the Government, and there are many factors outside the ALRC’s control that influence the Government’s ability and proclivity to implement recommendations.