19.12.2019

On 15 November, the ALRC released a Discussion Paper as part of its Corporate Criminal Responsibility Inquiry. In the Discussion Paper, the ALRC proposed reforms to individual liability for corporate criminal conduct. The proposals are set out in Chapter 7 of the Discussion Paper, and a shorter summary is available here.

These proposals respond to stakeholder concerns that the current regulatory framework undermines genuine efforts at compliance by individual corporate officers, while simultaneously failing to hold errant senior executives to account.

One of the key objectives of these proposals was to ensure that senior executives – including the CEO, CFO, and heads of department – can be held accountable for corporate misconduct, in light of their critical role in managing the conduct of the corporation (or the parts for which they have oversight). Compared to directors, who are already subject to considerable regulation, ‘C-suite’ executives (and those senior executives immediately below them) are less likely to be held responsible for corporate misconduct, despite often being in a position of greater influence over the day-to-day operations of corporations.

In preparing the Discussion Paper, the ALRC considered various approaches to individual liability for corporate misconduct that might address this gap, including variations on managerial liability, deemed liability, and a ‘failure to prevent’ approach. The ALRC also considered an approach modelled on the Banking Executive Accountability Regime (BEAR), which commenced in 2018 and applies to Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions (ADIs), which are licensed financial and banking institutions.[i] Given the infancy of that regime and the reservations expressed by stakeholders, the ALRC did not pursue that approach in the Discussion Paper.

However, the ALRC considers it may be helpful for stakeholders reviewing the Discussion Paper to revisit the BEAR approach, particularly in light of the decision earlier this week by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) to commence an investigation into possible breaches of the BEAR by directors and senior officers of Westpac.[ii] To the ALRC’s knowledge, this is the first such investigation of a corporation or its officers under the new regime, and as such will be closely watched.

What has the ALRC proposed?

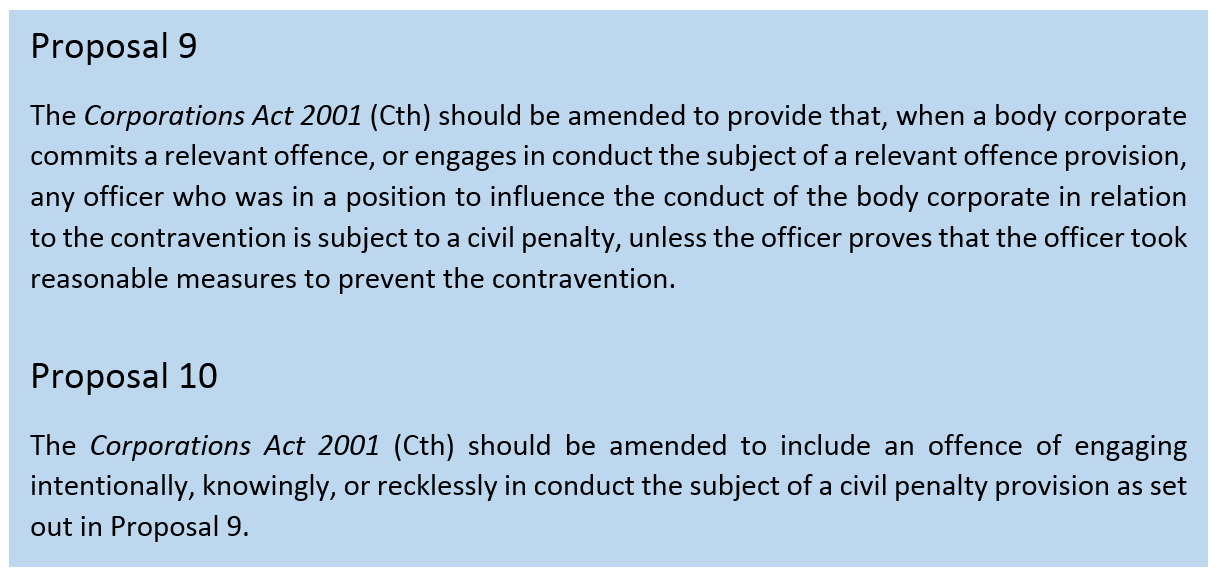

The ALRC’s proposals would make an executive officer liable for a civil penalty where they were in a position to influence the conduct of a corporation in relation to an offence, and they cannot prove that they took reasonable measures to prevent that offence.

What is the BEAR?

Under the new regime, ADIs must identify ‘accountable persons’ within the corporation, and provide documentation identifying these persons and their respective responsibilities to the regulator (APRA). An ‘accountable person’ is any person who, as a result of their position in the ADI or a subsidiary, has actual or effective senior executive responsibility for management or control of the ADI, or a significant or substantial part of the operations of the ADI or group.[iii]

The Act additionally sets out various responsibilities that may be identified with an accountable person, such as senior executive responsibility for anti-money laundering, compliance, internal audit, or overall risk controls.[iv] ADIs must ensure that all aspects of their business operations are covered by one or more accountable persons, and that those persons have clear lines of responsibility.[v]

The regime sets out specific obligations for accountable persons in the performance of their responsibilities (which are similar to the obligations of the ADI itself under the regime). These include:

- Acting with honesty and integrity, and with due skill, care, and diligence;

- Dealing with APRA in an open, constructive, and cooperative way; and

- Taking reasonable steps in conducting their responsibilities to prevent matters from arising that would adversely affect the prudential standing or reputation of the ADI.[vi]

‘Reasonable steps’ include – but are not limited to – implementing or overseeing:

- Appropriate governance, control, and risk management;

- Safeguards against inappropriate delegations of responsibility; and

- Appropriate procedures for identifying and remediating problems that do or may arise in relation to the matter.[vii]

How does the BEAR relate to the ALRC’s proposals for individual liability?

There are some clear overlaps between the BEAR and the ALRC’s proposals, including the obligation of senior executives to take reasonable steps or measures to prevent misconduct by the corporation and to ensure that appropriate compliance and risk-management procedures are in place. Both approaches also reflect an expectation that senior executives act with honesty and due diligence, though these standards are incorporated in different ways.

The ALRC has proposed a form of functional managerial liability, in which any senior officer who was in a position to influence misconduct in practice may be civilly liable unless they can prove that they took reasonable measures to prevent the misconduct. The BEAR, in contrast, adopts a hybrid form of liability that is both positional and functional: accountable persons are identified based on their position in the ADI, but liability arises in relation to the functional responsibilities of that person in the corporation.

Another key distinction is that while the BEAR creates stand-alone duties for accountable persons, the ALRC proposals would deem an executive officer liable where they have failed to prevent an offence by the corporation. The ALRC’s proposed liability model is tied to the corporation committing one of a specified set of serious offences. In that way, it is narrower than the BEAR, which creates standalone duties and does not expressly require the ADI to have committed an offence in order for an accountable person to be in breach. At the same time, the ALRC’s proposed model may in fact be broader than the BEAR, as liability may attach to a broader range of corporate misconduct, and not just matters that would affect the prudential standing of an ADI.

Finally, in terms of enforcement, the BEAR provides that an accountable person found in breach of their obligations may be disqualified by APRA from acting as an accountable person. This may have serious consequences in preventing a person from taking on senior roles within an ADI. APRA may also make orders for reduction of an accountable person’s variable remuneration (bonuses). Only the ADI itself may be liable for pecuniary penalties.

The ALRC’s proposals, on the other hand, would make an executive officer liable for a civil penalty where they were in a position to influence the conduct of a corporation in relation to an offence, and they cannot prove that they took reasonable measures to prevent that offence. Additionally, where the officer has done so knowingly, intentionally or recklessly, they may be criminally liable.

Could the BEAR provide an alternative model for individual liability?

The BEAR has attracted a mix of supporters and detractors in its short life. In the Final Report of the Financial Services Royal Commission, Commissioner Hayne recommended that the BEAR should be extended to the superannuation industry, noting that:

Those responsibilities should either already be identified or, at least, be readily identifiable. If that is correct, and it should be, preparation of accountability statements and accountability maps, though a burden, should not be a large burden. Performance of the obligations would then entail no reporting or recording beyond what prudent administration would require anyway.[viii]

However, early consultations raised concerns about the regime’s replicability beyond ADIs, particularly where business risk is not subject to prudential oversight. Concerns were also expressed about the administrative burden imposed by the regime.

While the current investigation by APRA into the conduct of senior executives at Westpac is unlikely to be concluded before the ALRC is due to report to the Attorney-General in April 2020, that investigation will nonetheless be closely watched, as it may provide valuable insight into the potential appropriateness or otherwise of extending the BEAR to non-financial corporations.

[i] Banking Act 1958 (Cth).

[ii] Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, APRA launches Westpac investigation and increases capital requirement add-ons to $1 billion, APRA (17 December 2019), <https://www.apra.gov.au/news-and-publications/apra-launches-westpac-investigation-and-increases-capital-requirement-add-ons>.

[iii] Banking Act 1958 (Cth) s 37BA(1).

[iv] Banking Act 1958 (Cth) s 37BA(3).

[v] Explanatory Memorandum, Treasury Laws Amendment (Banking Executive Accountability and Related Measures) Bill 2017 (Cth), [1.11]–[1.13].

[vi] Banking Act 1958 (Cth) s 37CA. The responsibilities of ADIs are set out in s 37C.

[vii] Banking Act 1958 (Cth) s 37CB.

[viii] Financial Services Royal Commission, Final Report of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (2019) 265.