19.11.2019

Research and consultations in the course of the ALRC’s Inquiry into Corporate Criminal Responsibility have highlighted the important role played by senior management in ensuring compliance throughout the different parts of a corporation. While corporations can be ‘a person’ under law, they are also made up of individuals – some of whom have authority and capacity to direct conduct on behalf of the corporation.

Stakeholders have expressed concern that the current regulatory framework establishing individual liability for corporate conduct both undermines genuine efforts at compliance, while simultaneously failing to hold errant senior corporate officers to account.

In particular, the ALRC is concerned that the current framework does not adequately address the responsibility of senior officers that oversee business models predicated on unfair or exploitative practices.

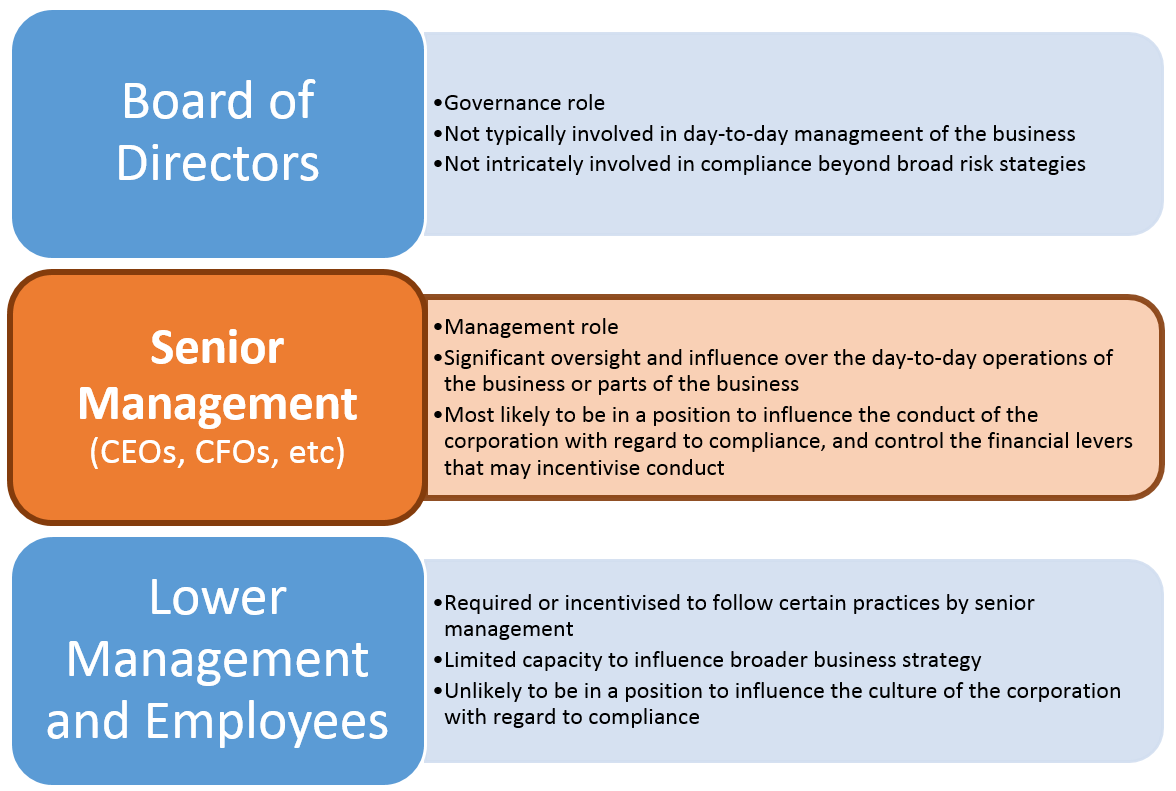

The ALRC agrees with the view that directors may not be the most appropriate focus with respect to compliance in the day-to-day activities of corporations, and as such does not propose any changes to directors’ liability. In contrast, the proposals focus on those senior officers (CEOs, CFOs, heads of department, etc) who are in a position to influence the day-to-day conduct of corporations.

The current law

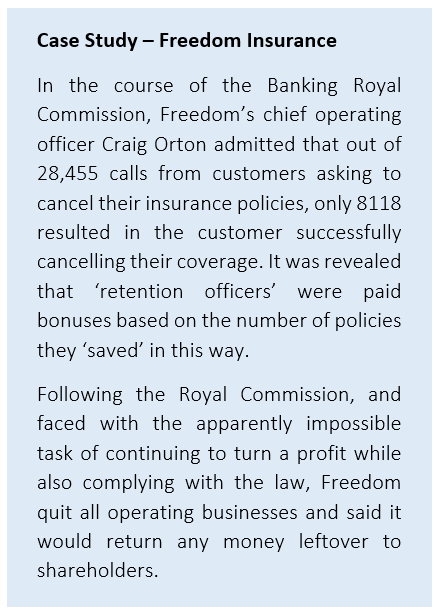

In order to better understand the current regulatory framework applying to individuals in the context of corporate misconduct, the ALRC reviewed a set of 25 key Commonwealth statutes that are relevant to corporations. Of those, the ALRC identified 26 provisions in 18 statutes that currently make an individual (typically an officer or executive officer) liable for an offence committed by the corporation.

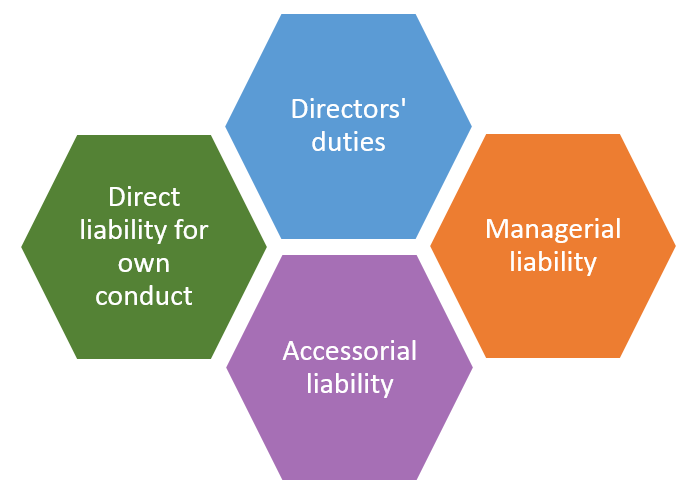

This type of liability is distinct from accessorial liability, in that the officer need not be directly or indirectly involved in the conduct constituting the contravention. It is also distinct from directors’ duties, which set out specific positive obligations for persons engaged in the position of director.

Instead, these lesser-known managerial liability provisions make an officer liable for a contravention committed by the corporation as a result of the officer’s position within the corporation.

An array of inconsistent liability provisions

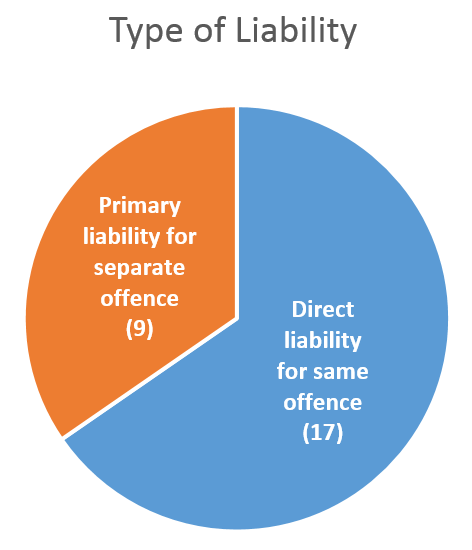

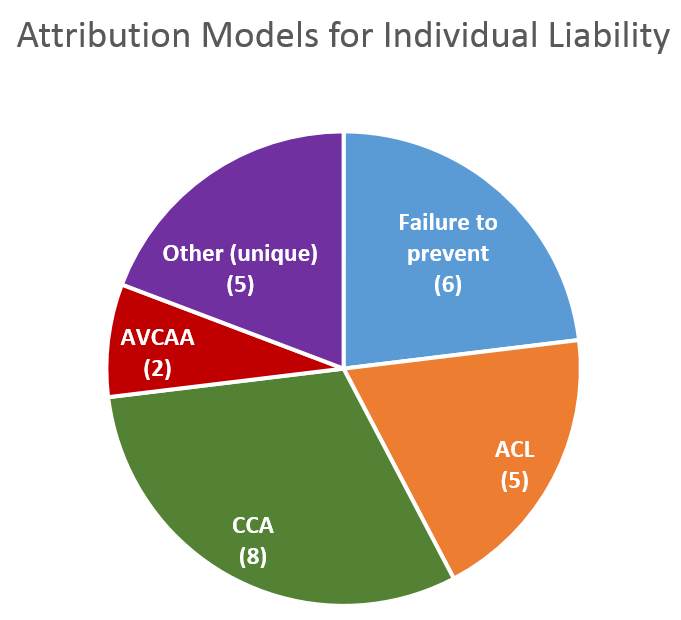

Many of these managerial liability provisions create deemed (direct) liability, under which the individual is deemed – based on their position in the corporation – to have engaged in the conduct and is liable accordingly. Others make an individual liable for a separate offence of failing to prevent a contravention by the corporation.

For the purpose of analysis, the ALRC identified four categories of managerial liability, and found a wide spread of each throughout the 18 statutes reviewed. (These categories are explained in detail in the Discussion Paper and Appendix I.)

Section 8Y of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth), for example, applies to a ‘person (by whatever name called and whether or not the person is an officer of the corporation) who is concerned in, or takes part in, the management of the corporation’. That section provides that, where a corporation commits a taxation offence, such a person ‘shall be deemed to have committed the taxation offence and is punishable accordingly.’

In contrast, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) creates a separate offence where an executive officer, who was in a position to influence the conduct of the body corporate in relation to conduct that contravened a provision of the Act, failed to take ‘all reasonable steps to prevent’ the contravention. Unlike the provision under the Tax Act, this offence also includes a fault element, requiring that the individual had knowledge of the contravening conduct, or was reckless or negligent as to whether the conduct would occur.

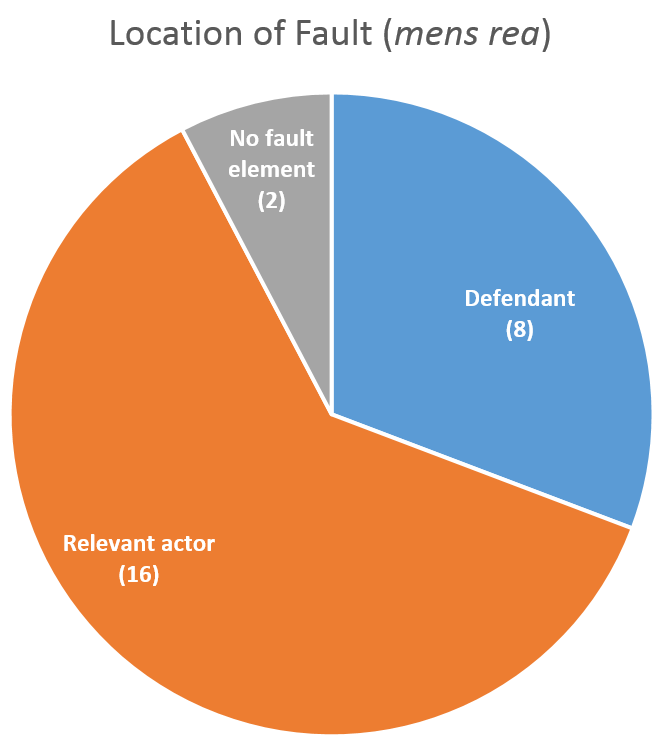

Less than a third of the managerial liability provisions identified by the ALRC require proof of fault on the part of the officer to be held liable. Most only require that the person who engaged in the conduct (individual or corporate) satisfied the relevant fault element.

A streamlined approach

The ALRC considers that some form of deemed liability – as presently exists in 18 Commonwealth statutes – may be an important tool in ensuring that those individuals who have a key role in encouraging and overseeing compliant conduct within a corporation are personally responsible for that conduct, and therefore improve corporate compliance with the law. Accordingly, the ALRC is attracted to models that posit liability based on an individual’s capacity to influence the criminal conduct that occurs, rather than the person’s formal title or designation. The ALRC considers that there is value in rationalising the current variety of managerial liability provisions into one common formulation, to be applied wherever it is appropriate.

Importantly, the proposals do not introduce a new kind of liability – they simply harmonise 26 distinct existing sources of liability and propose a more general application. This would make it easier for officers to understand and comply with their obligations.

Who may be liable under the proposed approach?

The proposals are framed to ensure that liability only attaches to officers in a position of sufficient influence and involvement in the day-to-day affairs of the corporation such that they should be expected to meet certain standards in the prevention of misconduct within the parts of the corporation under their management.

That is, the proposals reflect the position that senior managers – including the CEO, CFO, and heads of department – have greater capacity to ensure compliance throughout the corporation than the board of directors per se, whose role is one of governance, more than management.

This represents a narrowing of liability compared to the current deemed liability provisions, many of which purport to impose liability on any ‘officer’ of the corporation, which could potentially include both directors and lower level employees.

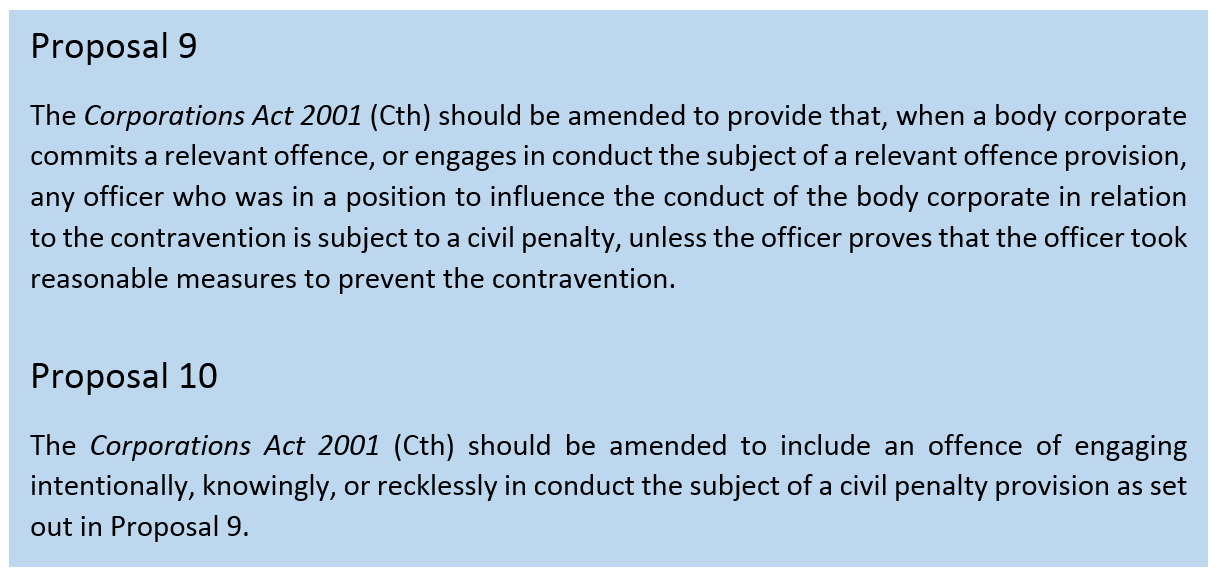

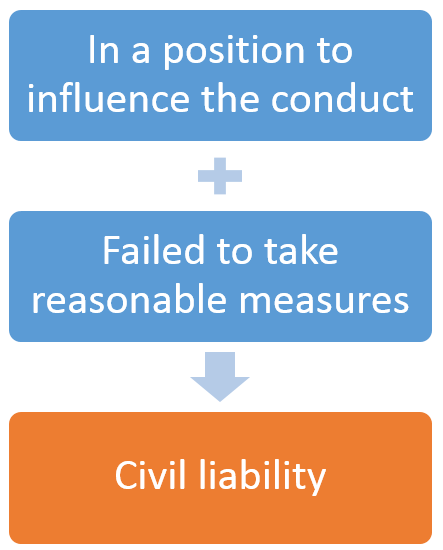

Under the proposed approach, liability would only attach to persons who meet the threshold requirement of ‘being in a position to influence the conduct of the body corporate in relation to the contravention’. Where prosecutors can prove that an officer was in such a position of influence with respect to a contravention by a corporation, that officer may be civilly liable, unless they can prove that they took ‘reasonable measures to prevent the contravention’.

The approach provides a clear defence for officers who genuinely endeavour to prevent misconduct in the parts of the corporation that they manage, in that they need only demonstrate that they took ‘reasonable measures’ to prevent the misconduct. Under the current law, we should already expect that any senior corporate officer is taking reasonable measures to ensure compliance in the parts of the corporation that they manage. Accordingly, the proposals do not involve any new form of liability, or impose any new obligations or burden on officers in relation to corporate fault.

Limitation on criminal liability

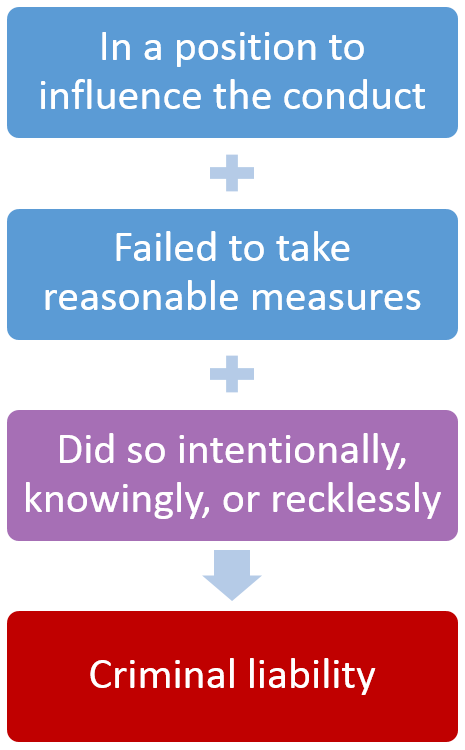

Under Proposal 10, individuals will only be criminally liable for the conduct of the corporation where they:

- meet the threshold requirement of being in a position to influence the conduct of the body corporate in relation to the contravention;

- failed to take reasonable measures to prevent the contravention; and

- did so intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly.

Compared to many of the existing managerial liability provisions – such as s 8Y of the Tax Act – this offers clearer protection for officers who have acted honestly and genuinely attempted to ensure compliance throughout the parts of the corporation over which they have influence.

Questions for further consideration

This issue is the subject of ongoing consideration by the ALRC, and submissions from the public are very welcome. In particular, in the Discussion Paper the ALRC asked whether these proposals should apply to ‘officers’, ‘executive officers’, or some other category of persons, and whether there are any existing deemed liability provisions in particular statutes that should not be replaced by the common formulation proposed, for any reason.