27.11.2019

In its Discussion Paper on Australia’s corporate criminal responsibility regime, the ALRC proposes a simplified method for attributing criminal responsibility to corporations. What follows is a short summary and explanation of the key principles underlying that proposal.

The law treats corporations as ‘people’. Therefore, the prohibitions imposed on people are usually applicable for both humans and corporations.

Corporations, by their very nature, operate, act, and think through human actors.

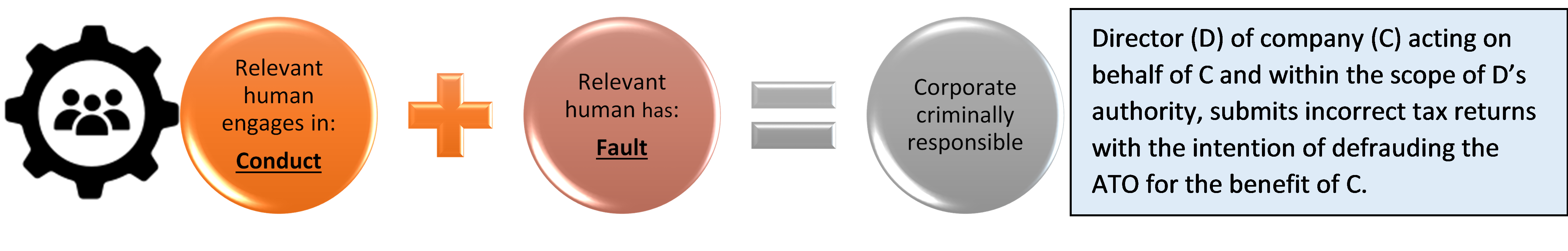

A key difficulty for imposing criminal liability upon corporations is that generally a corporation commits acts or omissions through humans. So, for a corporation to be held responsible for a crime, the elements of the crime (physical/conduct and mental/fault) are typically committed by a relevant person and attributed to the corporation.

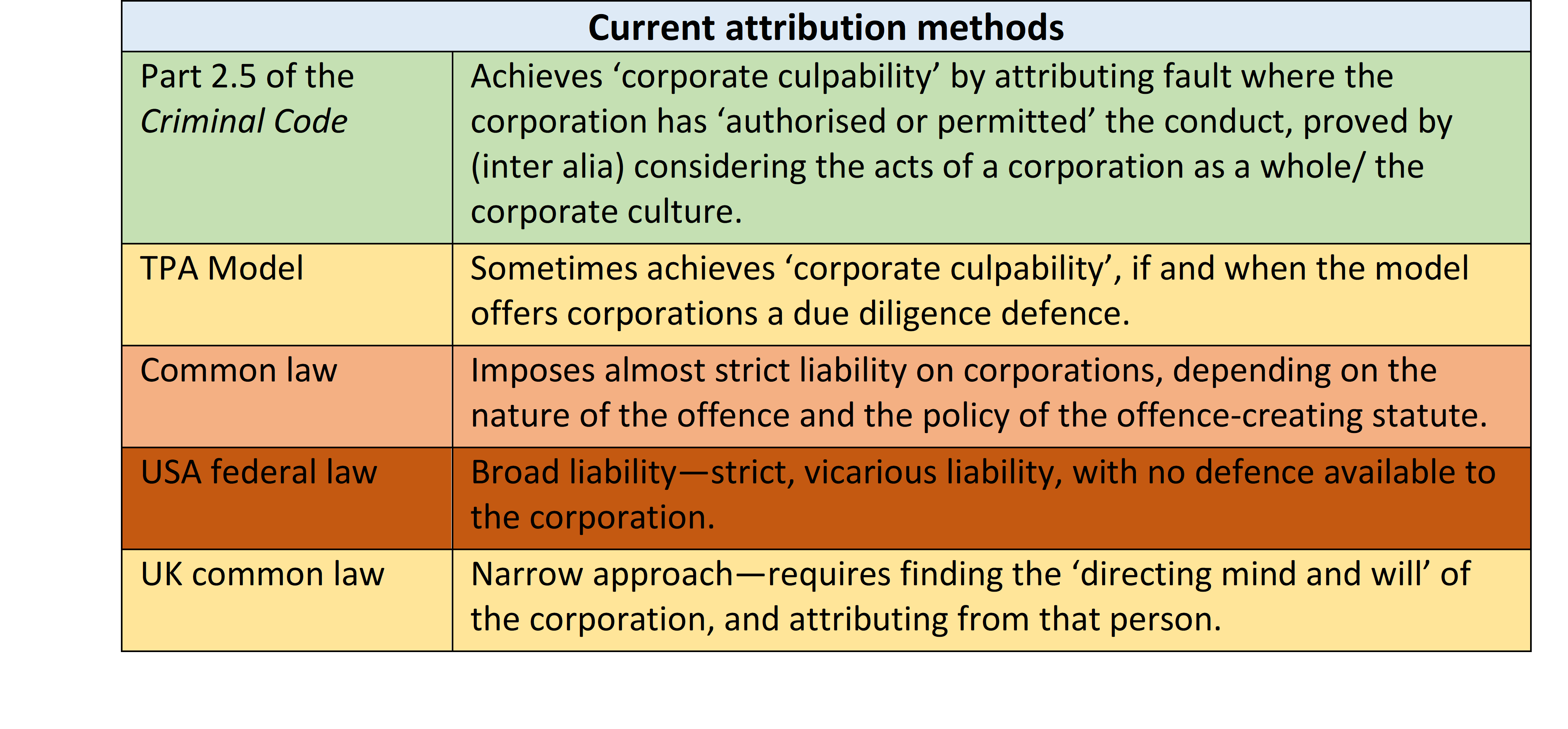

The Australian Commonwealth law contains essentially three methods of attribution:

- Part 2.5 of the Criminal Code;

- a smorgasbord of statutory attribution provisions, which generally have common characteristics (the ALRC refers to this as the ‘TPA Model’ in the Discussion Paper); and

- the common law.

The TPA Model applies to 88% of the legislation reviewed by the ALRC and is therefore clearly the most common statutory attribution method across the Commonwealth. The ALRC considers that Part 2.5 is a narrower attribution method as the prosecution must prove that either a ‘high managerial agent’ had the requisite state of mind or the corporation otherwise permitted or authorised the conduct. In contrast, while the statutory attribution methods vary, the TPA Model typically attributes conduct of directors, employees or agents, acting within the scope of their actual or apparent authority, to the corporation.

Simplicity

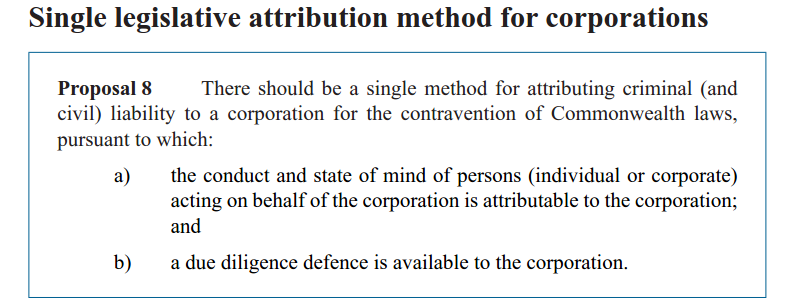

The ALRC considers that there should be one single statutory method of attribution under Commonwealth law. Multiple attribution methods create complexity and uncertainty.[1]

The ALRC considers that the proposed single method of attribution should combine aspects of the current attribution methodology under Part 2.5 and the TPA Model. In addition, the ALRC proposes two key principled changes:

- attributing conduct and fault from ‘associates’; and

- incorporating a due diligence defence.

Substance over form: ‘associates’

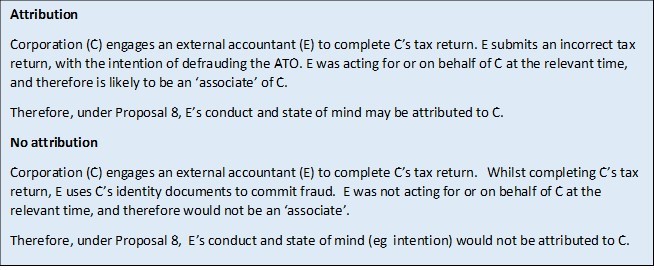

- The ALRC proposes attribution based on the substance of the relationship between the person and the corporation rather than the title or role of the person:

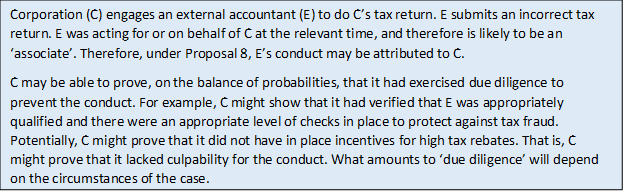

associate: any person who performs services for or on behalf of the body corporate

- A broad definition of associates is appropriate to reflect the nature of contemporary corporate business, which may utilise a variety of legal structures to operate (for example, contractors and subsidiaries, rather than just employees or agents).

- Importantly, liability only attaches to conduct engaged in for or on behalf of a corporation; the company would not be responsible for all behaviour of persons who are working for or who are otherwise merely associated with the company.

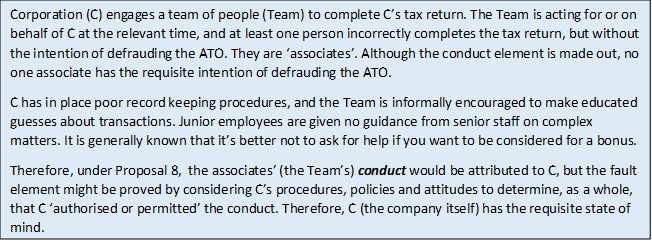

- Fault can also be proved by reference to the conduct of the corporation as a whole, that is if a corporation ‘authorised or permitted the conduct’. This preserves the language which precedes the corporate culture provisions in Part 2.5. Thus it remains open to a prosecutor to prove that a corporation authorised or permitted the conduct, by reference to a particular corporate culture.

The importance of blameworthiness: the due diligence defence

- In considering the principles underpinning corporate attribution, it is the ALRC’s view that it is essential that corporations be culpable before they are criminally responsible. Pure vicarious liability on the basis of conduct of certain individuals is insufficient.

- Where fault is being attributed from an individual, a corporation should be afforded a defence to prove a lack of culpability, by proving (on the balance of probabilities) that the corporation is not blameworthy (i.e. that it took reasonable steps to prevent the conduct).

- Given corporate criminality only attaches to conduct which is engaged in by individuals acting on behalf of a corporation, if the corporation wants to assert that it should not be responsible for the actions of those humans, then it is appropriate for the burden of proof should rest on the corporation.

The prosecution must still prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that the person acted for or on behalf of the corporation.

- Corporations should have an overarching duty to exercise due diligence to prevent criminal activity being carried out in the course of their business activities, by their associates.

- This does not mean that a corporation is responsible for the associate’s personal conduct, or that a corporation is prima facie guilty if any criminality occurs in the course of business. Rather, it the ALRC’s view that a corporation should take reasonable steps to ensure that their business is conducted in accordance with law.

- Ordinarily, under the criminal law it is not appropriate to impose a legal burden upon a defendant. However, corporations are not humans. The same concerns which give rise to necessary criminal law protections for humans do not exist for corporations.

- A corporation does not require the same protections as an individual (due primarily to its inability to be incarcerated and access to greater resources than an individual).

- The very nature of corporations is such that it would be almost impossible for a prosecutor to find and bring evidence of the due diligence of a company.

- Importantly, the due diligence defence provides protection to corporations from the actions of rogue ‘bad apples’. The legal consequences should be very different for a corporation where a rogue call centre operator breaching both company procedures and the law to maximise their sales commission, and a situation where call centre operators are encouraged to maximise sales in breach of the law and where there is no internal sanction for sales completed in breach of the law.[2]

A principled simplification

- As the TPA Model applies to 88% of the legislation reviewed, a proposal to replace the TPA Model with Part 2.5 of the Criminal Code, would result in a significant narrowing of the attribution of the criminal law to corporations.

- To date, the ALRC has received no evidence to suggest this would be appropriate. There is no suggestion of a proliferation of successful prosecutions of companies under the TPA Model. To the contrary, it would appear that the public perception of corporate crime (and the evidence presented at the Royal Commission) far outweighs the number of prosecutions of corporations.

The ALRC invites submissions on all of the proposals made in the Discussion Paper, including the appropriateness or otherwise of the proposed attribution method, and encourages submissions that include a suggested attribution method.

[1] As a consequence the ALRC is also not in favour of specific failure to prevent offence at this stage.

[2] See the Freedom Insurance Case Study cited in ‘When Should Officers be Liable for Corporate Crime?’ (ALRC paper, 19/11/2019).