The New South Wales Select Committee on the high level of First Nations People in custody and oversight and review of deaths in custody (the ‘Committee’) has called on the NSW Government to take urgent action to address the disproportionate rates of incarceration of First Nations people in New South Wales. As the Chief Justice of NSW, the Honourable TF Bathurst AC, has recently made clear, First Nations peoples are ‘one of the most incarcerated people in the world’.

In 2020, the NSW Government to set up the Committee to inquire into, and report on, the ‘unacceptably high level of First Nations people in custody in New South Wales, the suitability of the oversight bodies tasked with inquiries into deaths in custody in New South Wales’, and other related matters. In its final report, published on 15 April 2021, the Committee recommended that ‘the NSW Government commit to the immediate and comprehensive implementation of all outstanding recommendations from the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report and the 2017 Australian Law Reform Commission’s Pathways to Justice – An Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples report’. The ALRC’s report contains 35 recommendations which aim to address the disproportionate rates of incarceration of First Nations peoples in Australia, improve equality before the law for culturally diverse litigants and increase justice reinvestment through the redirection of resources from incarcerations to prevention, rehabilitation and support.

According to the Committee, ‘a recurring theme in the submissions and oral evidence given by witnesses was the need for governments to fully implement … recommendations from the ALRC Pathways to Justice report’. The Committee, echoing a submission from the NSW Bar Association, drew attention to 10 priorities in the ALRC report that need to be urgently addressed by the NSW Government. These priorities are:

- the establishment of an independent justice reinvestment body, overseen by a Board with First Nations leadership, and the initiation of justice reinvestment trials to promote engagement in the criminal justice system;

- the establishment of properly resourced specialist First Nations sentencing courts, to be designed and implemented in consultation with First Nations organisations;

- repeal of mandatory or presumptive sentencing regimes which have a disproportionate effect on Aboriginal offenders;

- the expansion of culturally appropriate community-based sentencing options;

- the diversion of resources from the criminal justice system to community based initiatives that aim to address the causes of Indigenous incarceration;

- the revision of bail laws to require bail authorities to consider cultural issues that arise due to a person’s Aboriginality;

- raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility and the minimum age of children in detention to 14;

- the abolition or restriction of offences relating to offensive language to genuinely threatening language;

- fine defaults not resulting in imprisonment; and

- the introduction of specific sentencing legislation to allow courts to take account of unique systemic and background factors affecting Indigenous peoples.

The Committee, in its eighth recommendation, also supported the ALRC’s recommendation for bail legislation to require bail decision makers to take into account any issues that arise due to the person’s Aboriginality. The Committee specifically recommended that the NSW Government amend the Bail Act 2013 (NSW) to include a standalone provision that parallels section 3A of the Bail Act 1977 (Vic).

In general, the Committee found that the historical, social and economic drivers contributing to disproportionate incarceration rates for First Nations people still exist, and this is, in part, because there is ‘no clear, transparent monitoring or reporting on the implementation of recommendations’. According to the Committee, it is ‘extremely disappointing’ that many of the recommendations made in influential reports, such as the ALRC report, have not been implemented, and 30 years on from the Royal Commission into Indigenous deaths in custody, ‘we are no closer to addressing the over-representation of First Nations people in the criminal justice system’. Fortunately, as Mr McAvoy SC submitted to the Committee, the royal commission report and the ALRC report ‘in themselves provide a guide for the States and the Commonwealth’ as to how they might address the systemic issues relating to over-incarceration.

The NSW Government is yet to respond to the final report. View the Committee’s final report.

View the ALRC Pathways to Justice Report, and the summary report.

On 28 October 2020 the Law Council of Australia hosted an online webinar, “Closing the Justice Gap: Implementing the Australian Law Reform Commission’s Pathways to Justice Roadmap”, which involved a panel discussion featuring eminent advocates and academics, Dr Hannah McGlade, Ms Cheryl Axleby, Dr Tracey McIntosh and Mr Tony McAvoy SC. Law Council President, Pauline Wright, moderated the discussion.

In this webinar, legal and policy experts discussed the report’s recommendations, priorities for implementation, and whether we already have a roadmap to meet the justice targets in the new National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

The Panel

Dr Hannah McGlade, Associate Professor at the Curtin University School of Law

Dr Hannah McGlade is a Noongar woman, and lawyer and academic from Western Australia. She is an Associate Professor at the Curtin University Law School, a member of the Medical Board of Australia and an expert member of the UN Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues. Dr McGlade has researched and published widely, served on many tribunals, boards and committees, led the development of legal support services and initiated many legal cases to improve recognition of rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Her work in Aboriginal human rights includes race discrimination, self-determination, state violence, prisoner’s rights, women and children’s issues, health justice and cultural safety. Dr McGlade was on the ALRC’s Pathways to Justice Advisory Committee.

Ms Cheryl Axleby, Co-Chair of Change the Record

Cheryl Axleby is a proud Narungga woman with family ties across South Australia (SA). Since 2012, She has held the position of Chief Executive Officer of the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement Incorporated, and she is currently Co-Chair of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (NATSILS).

Ms Axleby has over 25 years’ experience working within law and justice and has held the position of Chairperson of the Women’s Legal Service of South Australia, Alternate Deputy Chairperson of the then ATSIC Patpa Warra Yunti Regional Council, member of the Correctional Services Advisory Board to the Minister, and Board member of Dame Roma Mitchell. She currently holds positions as a board member of Seeds Of Affinity, Reconciliation SA, Justice Reinvestment SA Working Group, the SA Coalition for Social Justice, Tandanya Aboriginal Arts Centre and the Aboriginal Prisoners Offender Support Services in SA. Ms Axleby’s vision is for every Australian to be ‘proactive’ rather than ‘reactive’ to the issues impacting on the quality of life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Dr Tracey McIntosh, Professor at the University of Auckland

Dr Tracey McIntosh, MNZM, (Ngāi Tūhoe) is a sociologist and is Professor of Indigenous Studies and Co-Head of Te Wānanga o Waipapa (School of Māori Studies and Pacific Studies) at the University of Auckland. She was the former Co-Director of Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga New Zealand’s Māori Centre of Research Excellence.

In 2012, she served as the Co-Chair of the Children’s Commissioner’s Expert Advisory Group on Solutions to Child Poverty. In 2018-2019, she was a member of the Welfare Expert Advisory Group (WEAG) which released the report Whakmana Tangata: Restoring Dignity to Social Security in New Zealand (2019) and Te Uepū Hapai i te Ora- The Safe and Effective Justice Advisory Group which released two reports He Waka Roimata: Transforming our Criminal Justice System (2019) and Turuki! Turuki! Recommendations for Transformation (2019).

Dr McIntosh is the Chief Science Advisor for the Ministry of Social Development and she has recently been appointed as a Commissioner for the Criminal Cases Review Commission. She sits on a range of advisory groups and boards for government and community organisations and currently delivers education and creative writing programmes in prisons.

Her recent research focused on incarceration (particularly of Māori and Indigenous peoples) and issues pertaining to poverty, inequality and social justice. Dr McIntosh recognises the significance of working with those that have lived experience of incarceration and marginalisation and acknowledges them as experts of their own condition.

Mr Tony McAvoy SC, Barrister and Senior Counsel

Tony McAvoy SC is a Wirdi man from Central Queensland. He was admitted as a Barrister of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 2000, and made history in 2015 as the first Indigenous Senior Counsel in Australia. In 2018, he was awarded the QUT Outstanding Alumnus Award. Mr McAvoy SC has expertise in the areas of native title, human rights and discrimination law, environmental law, administrative law, coronial inquests and criminal law. Prior to becoming a barrister, Mr McAvoy SC worked in private practice, the Brisbane Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service, and in the New South Wales Government.

He has held many positions concerning Indigenous affairs and land rights, including the Registrar of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), Acting Part-Time Commissioner of the Land and Environment Court between 2011 and 2013, and Co-Senior Council Assisting the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory. He is Co-Chair of the Law Council of Australia’s Indigenous Legal Issues Committee, Chair of the First Nations Committee of the New South Wales Bar Association, Member of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration’s Council 2020-21, and Board Member of Griffith University’s new Climate Ready Initiative. Mr McAvoy SC was on the ALRC’s Pathways to Justice Advisory Committee.

Pauline Wright, Law Council President

Pauline Wright is a Partner Principal of P J Donnellan & Co Solicitors in Gosford. She was the President of the NSW Council for Civil Liberties from 2018 to 2019, having been Vice President since 1998, and has been active particularly in the areas of criminal justice, anti-terrorism and asylum-seeker policy. Ms Wright was President of the Law Society of NSW in 2017, having served on the Council of the Law Society of NSW since 1997. She also sits on a number of committees and working groups of the Law Council of Australia, including the Access to Justice Committee, Equal Opportunity Committee and the National Criminal Law Committee.

The Government is currently considering justice targets as part of a refresh of closing the gap.[1] In this context, last week Pauline Wright, President of the Law Council of Australia stated

The Government is currently considering justice targets as part of a refresh of closing the gap.[1] In this context, last week Pauline Wright, President of the Law Council of Australia stated

Governments must commit to the most ambitious justice targets possible, and to implementing the recommendations of the ALRC seminal Pathways to Justice report, which sets out the framework for how to achieve change.

In March 2018, the Australian Law Reform Commission report, Pathways to Justice–Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, was tabled in parliament. On the release of the report His Honour Judge Matthew Myers AM, Commissioner in charge of the Inquiry, said that while the problems leading to the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in prisons are complex, they can be solved

Law reform is an important part of that solution. Reduced incarceration, and greater support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in contact with the criminal justice system, will improve health, social and economic outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and lead to a safer society for all.[2]

Given the renewed focus on addressing the over-incarceration Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it is timely to consider the nature of the problems in detail and the solutions the ALRC identified.

The statistics

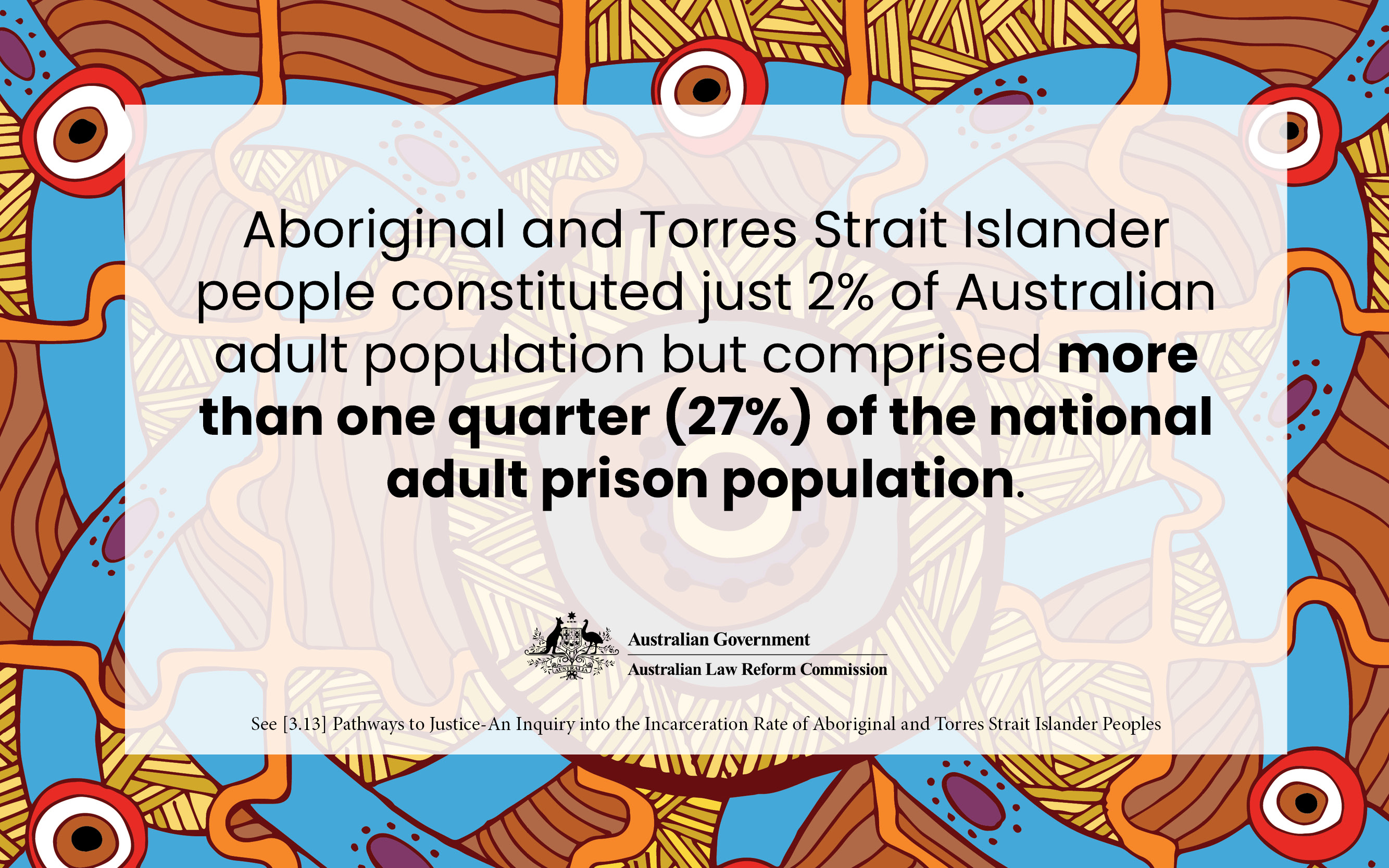

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the most incarcerated population on earth.[3] A December 2017 report by the ALRC found that while Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults make up around 2% of the national population they constitute 27% of the national prison population.[4] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are over-represented in our prisons by a factor of 12.5.[5] That is, an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person is 12.5 times more likely to be in prison than a non-indigenous Australian. The over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in our prisons is growing. In the decade to 2016, the over-representation grew from a factor of 11 to 12.5, while over the same period the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons in prison grew by 41%.[6] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are most significantly over-represented in our prisons by a factor of 21.2.[7]

Can these statistics be explained simply by the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians commit more crime?

No. Over-representation increases with the stages of the criminal justice system. In 2016, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were seven times more likely than non-Indigenous people to be charged with a criminal offence and appear before the courts; 11 times more likely to be held in prison on remand awaiting trial or sentence; and 12.5 times more likely to receive a sentence of imprisonment.[8] This means that even if we adjust for the increased likelihood of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person being charged with an offence, an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person is much more likely to end up in prison than a non-Indigenous person – the criminal justice system itself is disproportionately jailing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. We also know that the disparity in likelihood in being charged with a criminal offence is not simply about crimes being committed. We know that Indigenous people are more likely to come to the attention of police than non-Indigenous Australians.[9] In addition, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are less likely to be given a caution and are more likely to be charged than non-Indigenous Australians.[10]

Are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people more likely to go to prison because they commit more serious and violent crimes?

No. A detailed breakdown of the type of offence charged is provided by the ALRC, in the Pathways to Justice Report.[11] That report shows that such a simplistic assessment is not true. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are less likely to be charged with serious offences such as illicit drug offences and sexual assault and related offences than non-Indigenous peoples.[12] While a high percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are charged with offences within the category of ‘acts intended to cause injury’; 35% of these charges relate to ‘serious assaults not causing injury’. That is, in 35% of cases there was no bodily injury involved. [13]

Does Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status impact on sentencing?

Yes. An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person is much more likely to receive a sentence of imprisonment and much less likely to receive a community based sentence or fine than a non-Indigenous person.[14] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons are significantly over-represented in receiving short sentences of imprisonment, in part due to the unavailability or unsuitability of community based alternatives.[15] Short sentences of imprisonment are not only ineffective in reducing offending but are particularly damaging for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders. Short terms of imprisonment:

- expose minor offenders to more serious offenders in prison;

- do not serve to deter offenders;

- have significant negative impacts on the offender’s family, employment, housing and income; and

- potentially increase the likelihood of recidivism through stigmatisation and the flow on effects of having served time in prison.[16]

The imposition of a short term of imprisonment would appear to be inconsistent with the principle of ‘imprisonment as a last resort’ which ought to be reserved only for those offenders who represent a serious risk to the community, and for whom no other penalty is appropriate. Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders who receive a short sentence of imprisonment do so when convicted of minor or low-level offending.

Prisoners serving short sentences are less likely to be able to access programs or training, and in that regard, the time in prison does little to address offending behaviour or to develop skills that might later promote desistence from offending.[17] Offenders on short sentences are generally released into the community without supervision or supports to assist reintegration into the community on release.[18]

Way forward

While the Pathways to Justice Report paints a bleak picture as to the state of over-incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, it also suggests a way forward. The ALRC made 35 recommendations for reform to address the scourge of over-incarceration. Implementing these recommendations would:

- promote substantive equality before the law for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- promote fairer enforcement of the law and fairer application of legal frameworks;

- ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership and participation in the development and delivery of strategies and programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in contact with the criminal justice system;

- reduce recidivism through the provision of effective diversion, support and rehabilitation programs;

- make available to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders alternatives to imprisonment that are appropriate to the offence and the offender’s circumstances; and

- promote justice reinvestment through redirection of resources from incarceration to prevention, rehabilitation and support, in order to reduce reoffending and the long-term economic cost of incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[19]

[1] Tom McIlroy, ‘Closing the gap progress can’t take 73 years: Ken Wyatt’, The Australian Financial Review (3 July 2020).

[2] Australian Law Reform Commission, ‘Report: Pathways to Justice – Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ (Media Release, 27 March 2018).

[3] Thalia Anthony, ‘FactCheck Q&A: are Indigenous Australians the most incarcerated people on Earth?’, The Conversation (online, 6 June 2017) <https://theconversation.com/factcheck-qanda-are-indigenous-australians-the-most-incarcerated-people-on-earth-78528>.

[4] Australian Law Reform Commission, Pathways to Justice – An Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (Report No 133, 2017) 90.

[5] Ibid 95, Figure 3.2.

[6] Australian Law Reform Commission, Pathways to Justice – An Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (Summary Report No 133, 2017), 7–8.

[7] Australian Law Reform Commission (n 4) 98, Figure 3.5.

[8] Australian Law Reform Commission (n 6) 12.

[9] Australian Law Reform Commission (n 4) 451.

[10] Ibid 447.

[11] Ibid 100-102.

[12] Ibid 101, Figure 3.8.

[13] Ibid 101–2.

[14] Ibid 107.

[15] Ibid 230.

[16] Ibid 268.

[17] Mark Hughes, ‘Prison Governors: Short Sentences Do Not Work’, The Independent (20 June 2010).

[18] NSW expressly precludes prisoners serving prison terms of 6 months or less from parole supervision on release. See, eg, Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) s 46. The NSW Sentencing Council has recommended repeal or amendment of s 46: NSW Sentencing Council, Abolishing Prison Sentences of 6 Months or Less (2004) 5. Other jurisdictions restrict parole to prisoners sentenced to terms over 12 months: Crimes (Sentencing) Act 2005 (ACT) s 65; Sentencing Act 1997 (NT) s 53; Criminal Law (Sentencing) Act 1988 (SA) s 32(5)(a); Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic) s 11; Sentencing Act 1995 (WA) s 89(2).

[19] Australian Law Reform Commission (n 2).

The Australian Law Reform Commission report, Pathways to Justice–Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, was tabled in Parliament today.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men are 14.7 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous men. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 21.2 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous women. The ALRC was asked to consider laws and legal frameworks that contribute to the incarceration rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and inform decisions to hold or keep Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody.

Implementation of ALRC recommendations will reduce the disproportionate rate of incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and improve community safety. The 35 recommendations:

- promote substantive equality before the law for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- promote fairer enforcement of the law and fairer application of legal frameworks;

- ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership and participation in the development and delivery of strategies and programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in contact with the criminal justice system;

- reduce recidivism through the provision of effective diversion, support and rehabilitation programs;

- make available to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders alternatives to imprisonment that are appropriate to the offence and the offender’s circumstances; and

- promote justice reinvestment through redirection of resources from incarceration to prevention, rehabilitation and support, in order to reduce reoffending and the long-term economic cost of incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

His Honour Judge Matthew Myers AM, Commissioner in charge of the Inquiry, said that while the problems leading to the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in prisons are complex, they can be solved.

“Law reform is an important part of that solution. Reduced incarceration, and greater support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in contact with the criminal justice system, will improve health, social and economic outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and lead to a safer society for all.”

The Report represents findings from 11 months of research, 149 national consultations and more than 120 submissions.

Commissioner Myers expressed his gratitude to those who participated in the Inquiry.

“It has been humbling to meet with the community organisations and individuals who work tirelessly to achieve justice and better outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It is critical we acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples understand the problems leading to their over-incarceration. Facilitating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to develop and deliver appropriate strategies, initiatives, and programs are a feature of the ALRC recommendations.”

Pathways to Justice is available at www.alrc.gov.au/publications. A Summary Report is also available.

Transcript

Sabina Wynn (SW): Welcome to this podcast about the ALRC Report about the incarceration rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. I’m Sabina Wynn, the Executive Director of the ALRC, and I’m here with the Commissioner-in-Charge of the Inquiry, Judge Matthew Myers.

Commissioner Matthew Myers (MM): Sabina, thank you for having me. If I can firstly start by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we are meeting holding this podcast, the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation, and pay my respects to their Elders, past and present, and any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people listening to this podcast.

SW: So let’s talk about the context of the Report. There have been so many previous inquiries and reports into this matter. Why did we need this Inquiry?

MM: Look, you’re right. There have been a lot of previous inquiries. If we go back 26 years ago we’ve got the findings of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in Custody. And what we’ve seen since that time is a doubling in the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now held in prisons. We’ve seen a variety of things change. We’re now seeing for the first time that the biggest growth of people held in prisons are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women – that’s something that wasn’t occurring 26 years ago.

SW: The Report makes 35 recommendations that go to laws and legal frameworks, and I’m just wondering if you could speak a little bit about which of those recommendations will make the most impact in terms of lowering the incarceration rate?

MM: Sabina, if we look at the way in which people are offending, what the Report finds is that nearly half of all those Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people sitting in prison, are sitting in prison for low-level offending, sitting in their for repeat offending, where they’re churning through the system, coming in and out, in and out, for things like fine default, drivers licence problems, and a range of other things where they’re receiving sentences of two years or less. What our recommendations go towards are providing things like programs that address the problems these people are encountering, so that they don’t reoffend again, they’re not committing crimes in the community, and going back into prison.

SW: So what would be an example of a recommendation we’ve made that would address this low-level offending of people who are just going to prison for short-term sentences?

MM: If you look at recommendations around community-based sentences, where people who are offending and convicted get sentenced to go and do something in the community. If we take the driver licence example, be sentenced to get your driver licence. If you’ve got drug and alcohol issues, be sentenced to go and deal with those. In effect what we’re seeing is some of those community based sentences available across cities and big regional areas, but we’re not seeing those sentences available remotely. So the effect is magistrates or judges having to sentence people to prison because they haven’t got those alternative sentences available. So we’re making some recommendations that they be available so that people on short sentences can address their offending behaviour, so they don’t go to jail and just sit there. They actually do something about it so they don’t recommit crime.

SW: When we were travelling around the country consulting with stakeholders, many of whom were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and organisations, we repeatedly heard that it was crucial for the success of any program delivered for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, to have a leadership of those people, for them to be culturally appropriate and trauma informed. And I know there’s a lot of discussion in the Report about this. Can you just explain what we’re actually talking about there?

MM: Sabina, what we’ve seen over a good number of years is money being spent on programs delivered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that don’t work. Where somebody drives into town and says, we are here to provide to you this program, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people say, look – it’s not suitable for us. It’s not addressing the issues that we’ve got, and its not going to the crux of the problem. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people know well the problems that are facing their community. And what we have seen across the country are failures where they’re not consulted, where they’re not actually working on those issues themselves. But what we’ve also seen is the success of programs where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have leadership to address the problems in their community.

SW: You mentioned before the increasing rate of imprisonment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. What are some of the recommendations that might go to addressing that issue?

MM: Sabina, what we’re seeing are things done for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women that don’t fit. We’ve seen programs delivered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women that are really an adaptation of a program that is designed for male offenders that don’t translate very well or work. What we’re particularly seeing is a lot of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women come from backgrounds of extreme trauma, where they’ve been exposed to sexual abuse, family violence, a lot of them have post-traumatic stress disorder – things like that. So if you’re going to provide a program to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to prevent them reoffending, you need to take a trauma informed approach. In circumstances where they’ve suffered a lot of trauma, in circumstances where they’ve got particular needs that won’t be met by simple providing a male adapted program to them. So we’re really talking about programs that specifically meet the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women delivered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women themselves.

SW: So what are some of the other recommendations in the Report?

MM: We’re looking at things around Aboriginal Justice Agreements, where we get everyone involved in the criminal justice system to sit down together and work collectively for an outcome where they’re not just sitting in their sylos doing things remotely or in isolation, so we get better outcomes. We’re looking at police accountability. So – ways that police can better work with communities to do such things as reduce family violence, which reduced offending. Looking at courts, supporting courts that are delivering programs such as Murri Courts or Koori Courts, where we’ve seen things work, but aren’t being rolled out at the moment across the states or territories.

SW: It sounds like these recommendations could cost a lot of money.

MM: Sabina, I think we’ve got to look at the costs of incarceration. We’re talking about keeping someone in prison on average being about $300 a night. We know that collectively across the country we’re spending more than $3 billion a year keeping people locked up. What we’re seeing as well is that placing people in prison, where we don’t do anything to rehabilitate them does nothing more than presses the pause button on their offending behaviour. They go into prison, we take the pause button off, we let them out, and see them reoffend. It is a big cost to the community. But what I’m saying is there could be real savings made by doing something to prevent this reoffending behaviour taking place.

SW. We’ve now delivered the Report to the Attorney-General. Would you like just to explain what happens next.

MM: We’ve delivered the Report to the federal Attorney-General. But what you’ve got to remember is that a lot of the laws and legal frameworks that are driving some of this incarceration are state and territory based. So it will really be a matter for the state and territory governments to sit down together with the federal government to collectively work out what can we do to implement these recommendations and make some changes. But I guess, if I can say this before we finish. One of the leanings I made during the Inquiry was this. While the problems are complex and difficult, they’re not so big. In that the numbers of people locked up are not so great. We’re talking about, in Australia, a little bit more than 40,000 people locked up, of which about a little over 11,000 are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners. The numbers aren’t so great that we can’t do something about this and make a real change.

The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) today released a Discussion Paper, Incarceration Rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (DP 84), and is calling for comments and feedback on its questions and law reform proposals.

The Terms of Reference for this Inquiry ask the ALRC to consider laws and legal frameworks that contribute to the incarceration rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and inform decisions to hold or keep Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody. The ALRC was asked to consider a number of factors that decision makers take into account when deciding on a criminal justice response, including community safety, the availability of alternatives to incarceration, the degree of discretion available, and incarceration as a deterrent and as a punishment. The Terms of Reference also direct the ALRC to consider laws that may contribute to the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples offending and the rate of incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

Consultation sits at the heart of ALRC processes. The ALRC has conducted more than 100 consultations to date for this Inquiry which have informed the development of the questions and proposals. Following the release of the Discussion Paper, the ALRC will begin a second round of stakeholder consultations.

The ALRC invites submissions in response to the proposals, questions and analysis in the Discussion Paper, which is available on the ALRC website at www.alrc.gov.au/publications/indigenous-incarceration-rates-dp84.

Submissions are due to the ALRC by 4 September 2017.

The ALRC is required to present its Report on the incarceration rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to the Attorney-General by 22 December 2017.

To keep in touch with the Inquiry, please subscribe to the Inquiry e-news at www.alrc.gov.au/inquiries/indigenous-incarceration/subscribe

Meet the Commissioner

His Honour Judge Matthew Myers AM, newly minted ALRC Commissioner appointed to lead the Inquiry into incarceration rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, speaks about his journey in the law, and his perspective on this Inquiry.

- Listen to audio or read transcript >>

- See bio >>

Upcoming consultations

Consultation is always key to the ALRC inquiry process, and over the next couple of months, and again after the release of a Discussion Paper (end of June), we will be talking with a broad range of stakeholders including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their organisations, state and territory governments, relevant policy and research organisations, criminal justice and law enforcement agencies, legal assistance service providers, the broader legal profession, and community and non-government organisations. In February and early March we have been focusing on Sydney consultations (plus a day trip to Dubbo). This week we are in Brisbane for a few days, next week in Western Australia, then back to New South Wales briefly before heading to the Northern Territory for a week. Consultations in other states are in planning.

At the end of June we will release a Discussion Paper. This will include discussion of our research to date and proposals for law reform. The Discussion Paper will be accompanied by a formal call for submissions. The ALRC will embark on a second round of national consultations after the release of the Discussion Paper, seeking feedback on the proposals to assist in developing the final recommendations.

Advisory Committee

As indicated in our last enews, over the past few weeks we have been putting together an Advisory Committee, as per usual ALRC practice, to provide quality assurance in the research and consultation processes. The full Committee has not been finalised and a few positions remain to be filled. However we are happy to announce the following Advisory Committee members. We offer our sincere gratitude for their commitment to this Inquiry.

- Councillor Roy Ah See, Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Council, Central Coast

- Associate Professor Thalia Anthony, Faculty of Law, University of Technology Sydney

- Professor Larissa Behrendt, Director of Research at the Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning at the University of Technology Sydney

- Professor Tom Calma AO, Consultant, Canberra

- Josephine Cashman, Lawyer, Sydney

- Professor Chris Cunneen, School of Social Sciences, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, UNSW

- Professor Megan Davis, Indigenous Law Centre, University of New South Wales

- Geoff McKechnie APM, Assistant Commissioner, NSW Police Force

- The Hon Bob Debus AM

- Mick Gooda, Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in NT

- Adjunct Professor Russell Hogg, Crime and Justice Research Centre, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Victoria Hovane, Tjallara Consulting, Perth

- Tony McAvoy SC, Frederick Jordan Chambers, Sydney

- Dr Hannah McGlade, School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts, Curtin University, Perth

- Wayne Muir, CEO, Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service

- Susan Murphy, Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Council, Perth

- Commissioner Sally Sievers, Anti-Discrimination Commission, Darwin

- Professor Julie Stubbs, Faculty of Law, UNSW, Sydney

- George Zdenkowski, Magistrate and Adjunct Professor Faculty of Law, University of Tasmania, Sydney

- Pauline Wright, President, Law Society of New South Wales

Inquiry artwork

We would like to draw attention to the artwork, created especially for the Inquiry by Rachael Sarra, Goreng Goreng, artist and designer with Gilimbaa. The circular image at the top of this enews is a detail from the larger work, titled ‘A Pathway for Justice’, and represents the prison system. The yellow cross-hatching pattern, used here and sporadically in the full image, symbolises hardships faced by those in the system and a disconnection from culture. The complexity of the issues surrounding the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the criminal justice system and the journey towards justice are reflected in the puzzle motif and blue rivers in the full Indigenous Incarceration Inquiry Artwork. Read the Artist’s Statement for her interpretation of the artwork.

Welcome to the Inquiry interns

We are delighted that our call out to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander law students to participate in this Inquiry as legal interns attracted attention, and last week we warmly welcomed three Indigenous law students: Desiree Leha, Ganur Maynard and Noah Bedford from the University of New South Wales. These interns will work alongside the Inquiry team during Semester 1, assisting with legal research tasks, attending consultations and participating in team discussions.

Semester 2 presents another opportunity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander law students to be involved in this Inquiry, and we encourage any interested candidates to contact us directly.

Audio

Transcript

Sabina Wynn (SW): Hello I’m Sabina Wynn, Executive Director of the Australian Law Reform Commission. I’m here with Commissioner Matthew Myers who’s leading the current Inquiry in the Incarceration Rates of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Peoples. So Matt, welcome to the ALRC. I wondered if you could give us a little bit of your background, perhaps where you’re from and how you originally got into the law.

Commissioner Matthew Myers (MM): OK, I guess how did I originally get into the law? That’s an interesting question. Back in the late ‘80s my father and mother use to do some work with an Aboriginal pastor in Redfern—around a men’s shower and breakfast centre out of Elizabeth Street—called Bill Bird. During that time I would sometimes go with my dad down to Redfern and I remember going to a meeting in Eveleigh Street, which was what people use to refer to as ‘The Block’. It was a time where there was, what you could only really describe as over-policing of that area, and I remember walking down Eveleigh Street and seeing a police car pull up and there were some residents of Eveleigh Street really just standing in the street having a chat, minding their own business. The police car pulled up and wound its window down and started to ask some questions or give the residents a bit of a hard time and things started to get a little bit ugly. I was watching what was going on, not directly involved in it, and I saw a lady walk up. She spoke to the police and was completely respectful of them, but spoke to them and I guess you might say diffused the situation. Things could have gone badly but didn’t, and I didn’t really understand particularly what had gone on but had a chat to some of the people and it turned out that that person was a lawyer and I saw that as an enormously powerful thing, somebody coming in and intervening and fixing a situation that could have gone badly but didn’t. And the police moved on and the residents went about their business. At that stage I thought— that’s a really a powerful thing, that’s something I’d like to aspire to. I wasn’t so lucky to get the marks that I needed to get in law the first time and ended up going back and re-sitting the HSC and getting the marks then to get into law, so I’m a big believer in second chances.

SW: So then, after law school what area did you practice in?

MM: I ended up going into practice in a small law firm in a place called Terrigal which is on the central coast. And I was working there, and I’d worked there a little bit during my later part of university, and they offered me a full time job. And I remember doing bits and pieces, just seeing people, doing wills, doing odds and sods and one of the partners there did family law and he must have had a bad day in court because he came into me and said ‘I’ve had enough! I’m not going to do family law any more, you’re the family lawyer, you’re getting all the files’. Then his secretary came and dumped about 30 files on my desk and that was my baptism into family law.

SW: You’ve come to the ALRC from the Federal Circuit Court?

MM: I have. So I sit as a Judge of the Federal Circuit Court up in Newcastle and sit in a jurisdiction really just doing family law.

SW: The ALRC’s inquiry is about incarceration of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander people. You’ve been starting to talk to people, consult with members of community, the legal profession, the police—what are some of the things that you’re hearing that is contributing to the high rates of incarceration?

MM: It’s interesting, I think we are seeing common problems occurring commonly and I should be clear, this Incarceration Inquiry is not about excusing crime or being soft on crime. What it is trying to do is work out what is actually going on. For instance, we’re hearing from some of the people we’re having consultation with, you’re getting young kids or young adults in a set of circumstances, they’ve never been in problems with the police or the law before but for whatever reason it is they’re not in a position to be able to get a driver’s licence. And we had a consultation up in the country and some people said to us, ‘look they need to drive, they’re going to drive anyway, but there’s real barriers to getting those driver’s licences’, so for the first time we’re getting young adults who have never had a problem with the law before finding themselves breaching the law, getting themselves into trouble, and once they do then it’s a slippery slide, and then finding themselves incarcerated.

SW: Some people would be aware that there’s been a lot of work in the past about this sort of issue, we’ve had Royal Commissions, we’ve had other reports and reviews, there’s a lot of people who feel they’ve come up with a lot of the answers to this issue, what do you think the ALRC can add?

MM: The first thing is, we’re not starting at square one, what we’re doing is drawing upon all that work, looking at all those reports, inquiries, looking at Royal Commissions, trying to take out of that things that are relevant, I guess, to law reform. It’s a law reform commission, what can we do to try and change or reverse this trend by providing some real tangible, concrete recommendations around those things? It’s not about being soft on crime, it’s not about excusing criminal behaviour, it’s looking at how can we prevent criminal behaviour and prevent incarceration rates rising, how can we look at the system that we’ve got and provide some answers. Maybe if we did this differently we’d get a better result. Much like that example back in Redfern, there was a communication problem going on. Once it was resolved it then led to a situation where everybody was happy. So trying to work out what can we do around law reform, look at the laws, look at what we might do better. We’re very good in this society with telling people their rights, we’re not very good about telling people about their obligations, and we are probably even worse at helping people fulfil those obligations. We are going to be looking at what can we do around that sort of space.

SW: In terms of that, I suppose there are a lot of people doing good things but because we’re such a large country it’s hard to keep a track of everything.

MM: Well that’s right. Even at this early stage we’re seeing really good programs where we are changing people’s behaviour. All those programs are designed to reduce criminality, change people’s behaviours so that they don’t find themselves in jail, but you are right they’re often small programs in sometimes particular towns or particular states and because this country is so vast other people don’t know about it. So what we are hoping to do is thread together or tie together all the good work that’s been done, work out what’s not working, work out what is working and if we see a program that’s reducing crime rates which then leads to a reduction in incarceration, how can we take that program and adapt that, maybe, to a different state or across the board throughout the country, so we might see that as an answer. We are really looking at individualised programs and looking at the possibility of their adaption to the wider community.

SW: The ALRC will be putting out a Discussion Paper in the middle of the year and at that time calling for submissions. You‘re with the ALRC until the end of the inquiry in December.

MM: I am, so I’ll be here for the whole of the inquiry. We will be running consultations right throughout the year, so we are going to be meeting with people right throughout the year. That will be a really good point of the inquiry in the middle of the year— at about June where we’re going to provide a Discussion Paper— where we’re going to be saying, look here’s some of the things that we know about, here’s more questions, here’s a range of different things that we are finding out, let us hear what you might say about that. So go to the community and say to the community, the broad community, so police, people in education, people in the community, people working with prisoners in prisons, everybody, land councils, everybody, the whole community, what do you think about what’s going on? What do you thing about these questions? Do you want to provide even a written submission to us on it, so that we can actually find out what everyone’s views are? After we’ve spent the first part of the inquiry articulating or working out what are the real issues, what’s underlying this rate of over-incarceration? Why are these laws disproportionately affecting Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander people? Why are we seeing these high rates of incarceration?

SW: OK, good luck.

MM: Thank you, no doubt we’ll have further chats again.

SW: Absolutely, thanks Matt.

Welcome to the Inquiry

Today the ALRC received final Terms of Reference (TOR) for an Inquiry into incarceration rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Draft TOR were released by the Attorney-General’s Department for public consultation at the end of 2016, and the final TOR reflect much of the feedback that was received. The ALRC is to deliver its final report to the Attorney-General in December 2017.

- See AGD media release >>

- See Terms of Reference

The ALRC will undertake extensive consultation around the country over the next few months with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the legal profession and academics working in the area, and will work towards releasing a Discussion Paper containing proposals for legal reform in June.

The focus of this Inquiry, as set out in the TOR, is on finding the ways that law reform can help to address the unacceptably high rate of Indigenous incarceration, something that has been described as a national tragedy by the Attorney-General, Senator the Hon George Brandis QC. The ALRC acknowledges that much work has already been undertaken in this area and will have regard to the research, inquiries and reports concerning Indigenous incarceration that highlight the complex issues involved.

As is our practice, over the next few weeks, the ALRC will constitute an Advisory Committee for the Inquiry and will further develop our consultation strategy.

New Commissioner appointed to lead Inquiry

We are delighted to announce the appointment His Honour Judge Matthew Myers AM as an ALRC Commissioner to lead the Indigenous Incarceration Inquiry.

- See bio >>

- See media release >>

Opportunity for Indigenous law students

The ALRC is always keen to recruit Indigenous law students to its internship program, however we believe this Inquiry particularly offers a unique opportunity to learn about law reform and participate in the law reform process. We strongly encourage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander law students interested in working on this Inquiry, to contact us.

The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) welcomes the appointment by Attorney-General, Senator the Hon George Brandis QC, of His Honour Judge Matthew Myers AM as an ALRC Commissioner. Judge Myers will lead the new ALRC Inquiry into the high incarceration rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, announced by the Attorney-General in October 2016.

Judge Myers was appointed to the Federal Circuit Court of Australia in 2012. He is a member of the Board of Family and Relationship Services Australia, the CatholicCare Advisory Council (Broken Bay Dioceses), Law Society of New South Wales Indigenous Issues Committee, Federal Circuit Court of Australia Indigenous Access to Justice Committee, Co-Chair of the Aboriginal Family Law Pathways Network, member of the Central Coast Family Law Pathways Network Steering Committee, member of the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council, member of the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council, member of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples and member of the Honoured Friends of the Salvation Army.

Judge Myers said “I am honoured by this appointment and the opportunity to build on the valuable work of past Commissions, Inquiries and successful community initiatives. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men, women and children are significantly over represented in the Australian criminal justice system. This is something that cannot and should not be acceptable to any Australian. I look forward to undertaking a broad consultation across the country, working closely with stakeholders and the community to develop meaningful and practical solutions through law reform.”

ALRC President Professor Rosalind Croucher AM said, “We are delighted by this appointment and welcome Judge Myers to lead this very important Inquiry. To echo the Attorney-General, the over representation of Indigenous Australians in our prison system is a national tragedy. This Inquiry, with the expertise and leadership of Judge Myers, is an important step in developing much needed law reform in this area.”

The Attorney-General’s Department released draft Terms of Reference for Inquiry into the incarceration rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for community consultation, in December 2016. The consultation included Indigenous communities and organisations and state and territory governments.

The ALRC received final Terms of Reference on 10 February 2017.

The Terms of Reference require the ALRC to look broadly at laws and legal frameworks that inform decisions to hold or keep Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in custody and juvenile detention. The ALRC is to complete its report by 22 December 2017.

For information about the Inquiry please subscribe to Inquiry enews http://eepurl.com/cnIDFv.